|

Hanford: America’s Cold War Legacy

by Alan Sussex

Reprinted from The MENDONESIAN, February, 1997

"Wherever your people go, everything is destroyed" --- Yellow Hand, 1865

"Every part of this country is sacred to my people, the very dust responds more lovingly to our feet than to yours, because it is the ashes of our ancestors." ---Chief Seattle, 1854

The following figures of radioactive material discharged into the air, onto the ground, and into the Columbia River stated in this article may at times be staggering. Keep in mind that scientists are currently working on additional information as it becomes available from the DOE (Department of Energy), released under the freedom of information act known as the "Dose Reconstruction Project."

For example, the panel has yet to examine a 1949 experiment in which radioactive Iodine 131 and "other fission products" were released in a plume that extended as far as Spokane, WA. Keep in mind also that many of the figures are for releases prior to the massive high plutonium production years of the 1960’s and are supplied by the DOE itself. Therefore the numbers in this article may actually be understated and we may never really know the actual amounts of radioactive materials released into the environment at and from Hanford, whether by accident or as part of a planned release.

September 19, 1996, 3:00pm

I had just driven past the high school whose students are known as the "Bombers" and whose logo is a mushroom cloud. Passing Uranium Street, I pulled into the Atomic Market parking lot and parked in front of the Atomic Laundry.

This was my second visit to Richland and Hanford, located in southeastern Washington State. This time I would spend two days here and have a guided tour of the most contaminated, radioactive dumping grounds and plutonium production facility in America. We would visit nine plutonium production nuclear reactors, five immense plutonium extraction and equipment decontamination facilities, the "Tank Farms," consisting of 177 storage tanks that contain over 55 million gallons of very volatile and deadly HL (high level), RA (radioactive) waste, many of which are leaking, and also many surface dump sites known as cribs.

In early 1943, the U.S. Army hurriedly took over 640 square miles of land around farming villages of White Bluffs and Richland. Landowners were paid for their land and 1,500 residents given 30 days to get out. Native Americans like the Yakima and Nez Perce, who had traditionally fished and hunted here, were barred from the site. As part of the Manhattan project (an effort to build the world’s first atomic bomb), Hanford would become the site of the first plutonium producing "B" reactor. (The "B" reactor has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places and designated a National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark.)

This site was chosen next to the Columbia, Snake and Yakima rivers for the water needed to cool the reactor cores. Electric power was available from the Grand Coulee and there were rail lines along the Columbia. In 28 months 60,000 workers would build this massive complex and their living quarters in Richland, and produce the plutonium for the A-bomb dropped on Nagasaki. All in complete secrecy.

Eventually nine production and three experimental nuclear reactors would be built here, producing plutonium for over 70,000 warheads and hundreds of billions of gallons of RA waste. One commercial (electricity producing) reactor still operates today. All the others have been shut down.

|

All nuclear reactors discharge (RA) material into the air as a result of the chain reaction taking place within its RA core. In addition to this, eight of the on-line production reactors at Hanford were "single pass" or "open loop," which means they took water in from the river, pumped it directly around the hot RA core, and then dumped it back into the river. By 1960, RA waste water discharges into the river averaged 14,500 curies per day (exposure to tens of curies can endanger human beings). Fuel rupturing accidents caused water to come into direct contact with RA uranium, plutonium, tritium, strontium, cesium and other elements. Concentrations of radionuclides would dramatically increase in river water on these occasions as would the average yield of curies in later years.

From 1958 to 1964 the temperature of the river became so warm from the reactors that deep water was released from the Grand Coulee dam 50 miles up river on a regular schedule.

Estimates of RA gallons released from the reactors range in the billions of gallons; no exact figures are available. Peak years for RA water releases didn’t occur until the mid-60’s, but by 1947 some fish had concentration levels of 170,000 times that of the river water. The most basic organisms would absorb the Plutonium 239, Uranium 238, Strontium 90, Cesium 137 and other radionuclides. Then it would be passed on up the food chain, becoming more concentrated each time, so that by the time it reached the salmon, steelhead trout and whitefish it had become highly concentrated.

No estimate currently exists on the total amount of curies released during "normal" production or during core ruptures. (Columbia water was used downstream as a drinking source, to irrigate crops, water livestock and for swimming and recreation.)

After the nuclear reaction takes place in the reactor, a small amount of Plutonium 239 is created in the Uranium 238. The uranium rods are then taken over by rail to the extraction building ten miles away, where they are placed in nitric acid, which converts the uranium, plutonium and other elements into a liquid. From there, different chemicals are used to separate off the plutonium. As a result of these chemicals dissolving operations, vast quantities of RA gasses are formed.

These gasses were released on a regular basis when the winds were strong enough to carry them away from Hanford. In 1944 and 1945, 557,000 curies of radionuclides were released per year. Between 1944 and 1947, up to 270,000 men, women, and children living in ten counties and beyond were exposed to large doses of RA Iodine 131. It also landed on vegetation such as alfalfa, which was eaten by local dairy cows.

Infants fed milk were at greatest risk: a small number of infants may have received doses of 2,900 rads or more; about 1,400 infants and children in the area received from 15 to 650 rads; and up to 13,500 may have received doses of more than 33 rads from the milk they drank (one rad is the amount of radiation a body organ would absorb from about a dozen chest x-rays).

Information on other air releases is currently being studied for the content of RA materials and the amounts to which "down winders" were exposed.

The PUREX (Plutonium Uranium Extraction) building is as long as the Empire State

building is tall - over 800 feet. It is surrounded by three fenced rows of razor wire,

heat and motion sensors, and surveillance cameras. Like the other structures here, its

thick concrete and steel walls are designed to withstand heavy bombing. Called canyons

because of their immense openness inside, all five of these buildings are RA, from LL to

lethal. Well over 100 million curies exist inside their walls, ducting and filtering

systems.

The Plutonium-Uranium Extraction (PUREX) Plant, located in Hanford's 200

East Area, was constructed in 1953 with initial operation beginning in 1955. The building

is 120 ft x 1,080 ft, the size of three and a third football fields. The structure is made

of three components: a heaavily shielded process canyon; a pipe, sample, and storage

gallery section; and a steel and transite annex which house support services.

The PUREX solvent exraction (tributyl phosphate) system was operated from January 12, 1956 until the end of September 1972, to separate and decontaminate uranium, plutonium, and neptunium produced by the Hanford reactors.

Inside PUREX sits a 6,000 gallon mix of plutonium and uranium left over from when operations were shut down. (One millionth of a gram of plutonium will cause cancer if it gets into your body by breathing or ingesting, or by way of a cut.)

Up until 1955, PUREX produced on average 6.5 million gallons of high level RA waste per day before production dramatically increased.

One of the canyons is used to clean heavy equipment that comes into contact with RA material. Large amounts of water and chemicals are used in trying to reduce the radiation level of this equipment. Efforts are being made at Hanford to reduce costs whenever possible, so before disposing of expensive machinery by burying it in a "crib," attempts are made to "clean" it first, or at least reduce the radiation. Of course, this results in many millions of gallons of RA waste water.

Another canyon located in Area 200 is the Plutonium Finishing Plant (PFP). It is the final link in plutonium manufacturing at Hanford, processing plutonium-bearing solutions and converting them into metal oxide.

|

|

I had to laugh out loud at one point on the tour when I stopped to read the bulletin board in one of the buildings. One of the signs stated:

Warning: Important Information

Siren means a release has taken place.

Flashing Red Light means an air release has taken place.

Stop breathing.

Leave the area.

Create a barrier between yourself and area around you.

Obviously, I had a problem with the "stop breathing" part.

High level waste contains Plutonium 239, Strontium 90, Cesium 137, Tritium and other radionuclides, including many dangerous chemicals.

During these high plutonium production years of the 60’s, storage tank production could not keep up, so the HL RA waste was just disposed of on the ground. At Hanford, LL waste contains many of the same RA elements as HL waste, but in smaller quantities. It had always been dumped on the ground until the ground became "swampy" and dangerously high in radioactivity. (DOE has admitted dumping over 150 billion gallons of HL and LL waste on and in the ground at Area 200 at Hanford.)

After the ground became swampy, "injection wells" were drilled down, to near ground water level 250 feet below. For thirty years, LL RA waste was disposed of by just pouring it down these holes. As a result, surface soils in large areas are dangerous to be around even with protective clothing and special breathing apparatus.

As late as 1987, 6.2 billion gallons of RA liquid waste were disposed of on the soil. That yearly amount decreased to 1.5 billion gallons in 1994.

While the RA liquid waste was being disposed of this way, RA materials could evaporate into the air along with contaminated soil blown by the strong and persistent winds in this high desert area.

These winds are referred to by old timers as the termination winds. Workers constructing Hanford would last an average of 18 days before becoming fed up with being sand blasted and eating dust. I was told that every few years the winds reach 100 mph.

This windy area is the result of a combination of geological factors-mainly, the location of the surrounding mountains and the winds coming up the Columbia gorge.

Area 200 East and West also contain the HL RA tank farms, LL RA waste cribs, transuranic waste cribs(plutonium-contaminated) and many other miscellaneous dump sites. For instance, in one huge dug out section, I counted 60 center hull sections from nuclear submarines. Still radioactive, these missile firing and attack sub sections wait to be counted by Russian satellite under SALT I (Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty). Then they will be buried under soil.

In other small cribs I estimated at 300 feet long by 50 feet wide and 30 feet deep were RA concrete nuclear reactor sections, truck trailers, machinery and drums containing what, waiting to be covered. There are hundreds of cribs already covered with soil as this has been going on for over 50 years. They all contain RA waste, some with plutonium and other more dangerous radionuclides. For instance Plutonium 239 has a half life of 24,110 years, but will take well over a million years to totally decay. Tectretium 99, on the other hand, has a half life of 211,100 years, while Neptunium 137 has a half life of 2.14 million years. Many are a mix of chemicals, combustible materials and RA waste.

Early cribs were packed closely, causing their RA levels to approach spontaneous critical mass and subsequent explosion. These cribs were quickly "remined" and the RA material was redistributed further apart.

Near PUREX, long mounds can be seen; these are actually tunnels that cover underground rail lines. When items are too large and radioactive, they are loaded onto flat cars, pushed in by train and left there, flat car and all. When it rains, water perks through the RA cribs and soil, and is taken deeper towards ground water.

Area 200 East and West also contain the "Tank Farms," 177 tanks that hold over 55 million gallons of very volatile lethal liquid HL RA waste - over 500 million curies of the most deadly brew on earth.

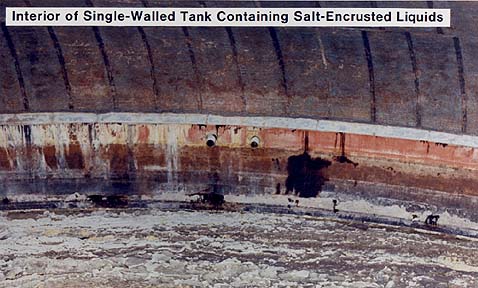

Varying in size from 55,000 gallons to 1.4 million gallons, 149 of the tanks are single-walled; of these, 67 have leaked or are suspected of leaking over 1 million gallons into the soil. All are buried in the ground 15 feet below the surface and encased in concrete up to 15 feet thick. In the 50’s, cooling pipes around some of the tanks broke during a freeze. Self boiling, hot thermal gasses inside the tanks could be heard banging and shaking them.

A frantic effort was made to stir this explosive stew before the tanks exploded, spreading this deadly material over a large area. A mixing device was created that was lowered into the tank. Today most of all the tanks still require mixing at a cost of almost $1.2 million per tank, per mix, to keep hot spots from developing within the tanks that can become a critical mass and explode the tank. (Critical mass can be attained with as little as 25lbs. of HL RA material. A spontaneous fusion chain reaction can occur, releasing a lethal shower of neutron and gamma radiation.) Explosive gasses like hydrogen form within this liquid that is sometimes the consistency of peanut butter.

High Level Radio Active waste.

Because of the decaying effect that RA material has on metal from constantly being bombarded with neutrons, tank life expectancy has been cut in half from 25 to 12 years on the older tanks, and, because there are no drains on the tanks, the material is difficult to transfer. Originally, the contents within the different tanks were in general kept separate, as there are a great many different kinds of volatile chemicals and RA materials involved. But once the tanks began to leak, it all became mixed together as they pumped from leaking to non-leaking tanks.

The contents can vary greatly in different areas, even within the tanks themselves. Some of the older tanks that we looked at were located in fields and had thick, rough concrete access lids while the new tank farms had concrete platforms and secured metal access lids. Tanks built after the mid-70’s are double-walled and made of combination of stainless steel and titanium. I was told they will probably last twice as long as the early tanks. There are 28 of those, the ones we looked at holding 1.4 million gallons each.

Many of the RA materials in these tanks and those which were poured on the ground when the tank space wasn’t available, will take over a million years to decay - Plutonium 239 - and others can take even longer. Meanwhile the potential for a catastrophic explosion is always nearby.

The "B" building is also in Area 200 (letter designations were given to the buildings for security reasons), where there are over 1,900 2 foot long cylindrical containers standing on end in racks 15 feet under water. Each contains extremely high concentrations of Strontium 90 and Cesium 137 isotopes that were removed from some of the HL RA storage tanks in order to reduce their heat and make them less volatile. So strong is the radiation from these containers that they glow a bright blue.

Over 100 million curies have collected inside the building itself, in the walls and ventilation system. I was told that a 60-second unprotected exposure inside this building would be lethal.

The K-basins are located on the northern edge of Hanford. Just a few hundreds yards from the Columbia river are two large concrete tanks 125 feet long and 67 feet wide. Inside the tanks are 4.6 million pounds of highly-radiated spent uranium rods containing plutonium(80 percent of the DOE’s inventory), some corroding and crumbling, that have spilled their contents into the protective water.

The tanks themselves are rusting and deteriorating rapidly. Sixteen feet of radiation-shielding water covers the rods to protect workers in the area. They have leaked over 15 million gallons of HL RA liquid, containing plutonium, strontium, cesium, tritium and other radionuclides, that is slowly seeping into the river.

I counted about 80 fishing boats just beyond the tanks that beautiful sunny day. As we walked away from this area an armed guard drove up to see what we were doing.

After 50 years of dumping more than 150 billion gallons of HL and LL liquid RA waste on the ground, and after 16 million gallons of HL leaks, the waste has traveled down 250 feet to ground water in Area 200 and moved to the east 15 miles in a plume that covers 200 square miles and is seeping in a 10 mile long front into the Columbia River. I counted over 100 fishing boats in a one mile section of this front.

Six other ground water locations are contaminated with HL and LL RA waste, three of which are seeping into the Columbia on the northern edge.

Millions of dollars have been spent on water filtration facilities that pump up chemically contaminated ground water, filtering it through a series of carbon filters and returning it to the ground where it is once again re-contaminated by the super saturated soils.

|

With the expense of containment being so high, attempts to deal with earthquake vulnerability is probably out of the question. An earthquake here is inevitable and the potential for a calamity exists that could leave a large portion of the United States uninhabitable.

Some of the buried tanks holding 55 million gallons of HL RA material could split, dumping their loads into the soil where, without the ability to stir or neutralize it, a spontaneous fusion chain reaction could occur, releasing a lethal shower of neutron and gamma radiation.

At the "B" building where the rods containing strontium and cesium are stored, containment pools could crack and lose their protective water. There, too, spontaneous fusion could take place as the rods now lay in a jumbled mass on the pool’s bottom. The K-basin tanks could split, spilling millions gallons of RA liquid almost directly into the Columbia river, while at the same time uncovering the crumbling, spent uranium rods with the same disastrous results.

Contaminated reactors and processing buildings might crack, allowing their RA contents out and the elements in. Dust from RA surface soils would be raise and carried by the wind - a catastrophe of unimaginable size and scope.

On Friday, Tom Grumbly, under-secretary for the DOE, came in to proclaim Area 1100 clean, the first site at Hanford to be taken off the EPA superfund list. He remarked on how wonderful it would be in ten years when all of Hanford would be clean and turned over for private use.

No mention was made that it was a truck maintenance and storage location and not contaminated with RA materials. Area 1100, now deemed safe and clean, will be turned over to the Port of Benton to be leased or sold to private developers.

I thought about the 55 million gallons of RA material in the Tank Farms, billions of tons in the buildings, cribs and soil, and the 200 square mile plume.

No, all of Hanford won’t be cleaned up in ten years or even a thousand years. There isn’t enough money in the world to do it, nor any place to put the waste. Where do you put trillions of cubic feet of RA soil and water? Parts of Hanford will have to be fenced off and declared a "National Sacrifice Area" for many thousand of years. It will have to decay on its own.

By the end of this year, nine billion EPA superfund dollars will have been spent here with little to show for it. The clean-up consists of mainly hurrying from one serious situation to another and trying to keep it from getting out of hand. In between "containment" is worked on by the over 14,000 employees. Another $100 billion is expected to be spent here in coming years.

With that kind of money flowing into this community of 140,000, the building boom is on again. All the giant retailers and malls are here, and three golf courses and large housing tracts are going up.

Little fear of Hanford exists in this very conservative, patriotic community after 50 years of being told "there’s nothing to worry about," and where almost every person’s job is connected to Hanford.

On what used to be part of the exclusionary zone at Hanford and only about five miles southwest of Area 200, an industrial park has been laid out next to the alfalfa fields. Across the road is a large up-scale housing development of more than 3,000 homes, including a golf course called Horn Rapids that winds its way among them. Motorhomes, boats and kids’ bikes are in the driveways. On the back of a brochure promoting home sales is the following:

The Yakima river meanders through an unspoiled landscape, bends and cascades over rocky shallows, and rising above the water is a stretch of land that takes it name from this work of nature, Horn Rapids, a place unlike any other.

On Friday a hot (RA) mouse set off alarms at the food bank building, where donated food is sent that has been collected from other onsite locations. It is then distributed to other offsite areas and given away to the mostly Mexican farm workers. The mouse was trapped alive by the special RA mouse/animal patrol and anesthetized, and an autopsy was conducted. They could tell by the RA isotopes it had absorbed that it had probably come from Area 200, 15 miles away, but they weren’t sure how. Most likely, it had arrived here in the boxes of food donated by the workers. Food will no longer be collected from Area 200.

All roadkill and other animals found dead at Hanford, like the deer and three coyotes I had seen earlier, are quickly picked up and inspected for the extent of RA contamination and its effects.

The wind whips up again as I drive past Area 200 for the last time heading towards Richland, blowing dust into the air and creating sand dunes next to the road. Another coyote dashes across the road in front of me, probably going to look for lunch at the Horn Rapids housing development on my right. The words from the brochure come back to me now: "this work of nature, a place unlike any other." The spirit of Dr. Strangelove is alive and well at Hanford. xxx

News Note: Los Angeles Times, July 26, 1997: Hanford Nuclear Reservation: The Department of Energy released a report detailing the May 14, 1997, chemical explosion of a 400-gallon storage tank that released plutonium and other hazardous chemicals in a yellow-orange air-borne plume that contaminated several workers, as well as spreading offsite and across a public highway. In addition, the DOE admitted a complete failure of their emergency-response plan and reaction.