Beneath Apache

Country: Inside

WIPP (Waste Isolation Pilot Project)

by Alan Sussex

Part Five

Heading toward the Brine Inflow Test Room Howard stops the cart where they have been boring into the salt. Getting out to take a closer look, I pick through the smaller chunks lying loose. Howard examines a number of them before handing me one that contains brine. Looking closely you can even see the tiny bubbles of brine trapped inside the salt.

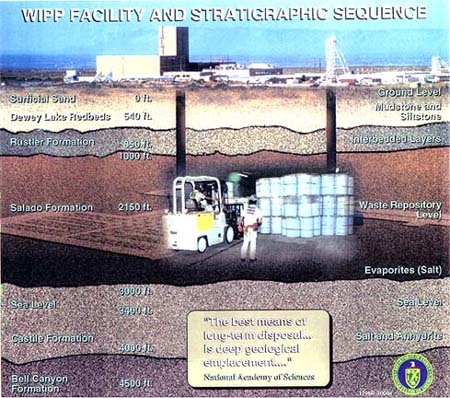

Walking back to the cart with the sample, he hands me a thick clear plastic ziplock bag to put it in. On it reads, " Permian Age Rock Salt - 225 million years old - from the WIPP storage level, 2150 feet underground." A souvenir.

On our way once again, the roar of the ventilation system is always around us. In moving through the 10 mile grid of salt storage tunnels, we need to stop occasionally at metal barriers that span the 33 foot wide, 13 foot high passageways.

It’s a rather tricky system, trying to create a seal between the ceiling that’s continually dropping down and the walls moving in. The metal framework has a thick rubber seal between it and the salt walls, while the frame is made of multiple sliding section; as the tunnel opening slowly gets smaller, so too will the framing.

All of the air ducting and electrical cables pass through the upper corner of this movable barrier.

The purpose of these dividers is to isolate the different sections of the underground grid system in the event of fire and smoke. It also serves to contain other fumes from the equipment that operates down here.

Coming to a stop in front of the divider, Howard pulls on a cord that hangs from the ceiling. A bell clangs loudly and a smaller section automatically slowly opens. Driving to the other side, Howard pulls another cord, the bell rings again and the door closes behind us.

Passing one of the idling, low-slung salt carrying vehicles, I’m hit with the heavy smell of diesel fumes. When I ask about the thick smell of exhaust, and the effects on the men working and breathing those fumes, Howard responds by saying that 3 times the amount of air is moved down here that OSHA requires for worker health and safety.

While that’s probably true, I still think to myself that while the air is moving, within it is stuff that you just don’t want to be breathing. Diesel fumes are much more dirty and harmful than that of gasoline.

Arriving at the Brine Inflow Test Room, I can see a round sealed hatch about six feet in diameter on the opposite wall, a few feet up off the floor. A stairway leads up to it. This perfectly round hole has been bored into the salt sloping slightly downward to the rear for 300 feet. The theory is that migrating brine will drip, to trickle down the round walls and then run down the gentle slope to collect in the rear of this tunnel, because the "room" is sealed airtight to keep other moisture out. A TV monitor is located on a table nearby. Howard operates the three remote cameras located inside.

Scanning different locations, he points out the crossed laser beams at different intervals within the bored tunnel. It’s like looking through the crosshairs of a rifle scope. The laser beams measure the movement of the walls coming in on themselves.

Every 4 to 6 months a team of men masked and dressed with portable breathing apparatus to keep themselves isolated, and from bringing in additional moisture, will enter this room to collect and measure the brine that’s accumulated at the lower end of the tunnel. Howard said that on the last trip they brought out something like a 1-1/2 liters that accumulated over a three month period.

While this procedure may give some idea of the amount of the brine within the salt beds at a given level, (i.e. 2150 feet), I again thought about the higher concentration of brine that exists under the 3000 foot thick layer of salt beds.

While Howard and Curtis seemed unaware of this pressurized brine, Mr. Wendell Weart, Manager, Waste Technology Department, Sandia Labs (Advisor to DOE), has acknowledged its existence.

Just as troubling as the existence of large pools of brine under the salt where WIPP plans to bury the plutonium-contaminated waste, is the Restler aquifer located 1-1/4 miles north of the WIPP site.

In 1981, EEG (Environmental Evolution Group) of Albuquerque, New Mexico, contended that they suspected such an aquifer existed below the surface and above the intended tunnel storage system. The DOE (Department of Energy) disagreed and a debate took place.

EEG is an organization comprised of independent scientists. Robert Neil, its director, tried to convince the DOE that they believed the aquifer existed. When the DOE failed to follow up on their advice, a well was drilled in November of 1981 striking the pressurized aquifer just below the surface, at 500 feet. Over one million gallons shot to the surface like a fountain, forming a small lake.

This Restler Aquifer feeds into the Pecos river that is used in Texas for drinking,

irrigation and for cattle and livestock.

After the discovery of this large body of water above the intended plutonium storage area,

the entire underground grid of planned for excavation was pivoted 180 degrees to the south

from the main elevator that we had come down on.

This places the Restler Aquifer 1-1/4 miles to the north of WIPP. As we walked away from the Brine Inflow Test Room, I thought of the collection of tiny amounts of brine from within the salt while above and below existed millions of gallons………

Part Six

As we drove away from the Brine Inflow Test Room, I continued to think about the ways that theplutonium-contaminated waste could find its way to the surface 2150 feet above and possibly into the Restler Aquifer.

40% of the waste will be comprised of combustible materials and, just as in a "surface" landfill, once buried these wastes will begin to decompose, giving off heat and gasses. In addition to this, the salt will creep in to entomb the 6.5 million cubic feet of toxic wastes. More than 2000 feet of salt will compress and pressurize these combustible materials.

Could radioactive particles contained in the wastes migrate to the surface and find their way into the Restler Aquifer or atmosphere? These thoughts flowed through my mind as we bounced along this salt roadway, through the dimly lit storage tunnels. My eyes and throat were beginning to burn more now from being down here within these salt beds. I stared at walls as we moved along, looking at the white streaks 6 inches to 1 foot long where brine had oozed out of the salt and run down the walls where it evaporated.

Howard broke my concentration by stopping the cart. He pointed out a 12-foot diameter shaft about 40 feet to our right that was bored to the surface from the bottom of the 2150 foot level. First a small 3 foot hole was drilled down from the surface into the previously excavated section of the salt. Then a 2150 foot long shaft was inserted. A 12-foot cutting device was then attached at the bottom of this shaft. All went well as this 12 foot hole was drilled from the bottom up until the diamond tips on the cutter began to dull as it neared the half-way mark - it could cut no further. When this huge drill bit was stopped, the salt crept in below the hole that had already been cut seizing the drill bit in place. It couldn’t be dropped down now because the hole had gotten smaller than the bit, nor could they go up because it was too dull to cut.

The shaft was withdrawn from the surface leaving the drill bit stuck in the salt, two men were lowered 1000 feet down this 3 foot hole to the bit where they changed the numerous diamond cutting teeth on it while still jammed in the salt.

I though about what it would have been like to be lowered down that small hole and then crawl around in near darkness changing those cutting teeth as the salt moved in. Not knowing if there would be some sort of collapse trapping you in there. The job was successfully completed, an experiment in new drilling technology. For the moment this shaft remains unused.

Moving along again I ask Howard if Apaches are on-site and working down here, he acknowledges that there are, but doesn’t know how many. From the time that the Spanish first arrived in the 16th century, the Apaches were used as slaves to mine for gold and silver on their own lands. Now they are hired to work in the nearby potash mines, or copper mines, and now these salt mines of sorts. Preparing what was once their sacred mother to be the repository for the most deadly substance on earth, Plutonium 239.

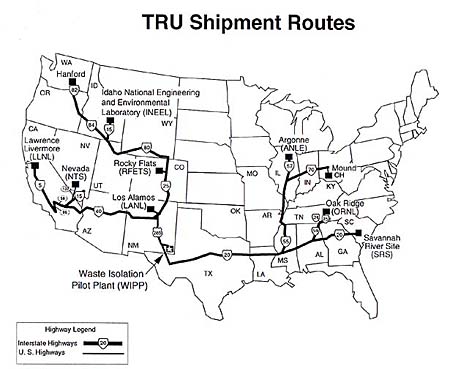

Some 30,000 truckloads (or more) of contaminated waste will head for Carlsbad, New

Mexico from all directions, traveling through towns and cities on highways with their

deadly loads that have a half-life of 24,000 years. These trucks will cross rivers,

railroad tracks, bridges, and will travel on freeways and pass through major intersections

of surface streets throughout the U.S. Almost every state will be crossed during

transport. The question is not whether there will be an accident involving these trucks

carrying this waste, but how many will there be? Will a truck be hit by a train? Or drive

off a bridge into a river?

Will the containers hold the plutonium from escaping if there is an accident? If not, entire areas would need to be evacuated and remain sealed off for possibly more than 20,000 years. Soon thousands of truck loads of waste will be crossing native lands around the country and converging on Apache country. 6.5 million cubic feet of waste will be destined for WIPP. 1/10 of 1% of the nation’s plutonium waste, 1/1000th of what currently exists (as more is being produced each day).

WIPP, or Waste Isolation Pilot Project, is just that, a "pilot project," for there is a need to find 999 other sites for the remaining 300 million cubic feet of waste. Some 40,000 tons of plutonium are in temporary storage - within ten years it’s predicted that it will rise to 80,000 tons and, with the dismantling of some of our nuclear weapons, an additional 120,000 tons of plutonium 239 will need to find a safe resting place. (One millionth of a gram will cause cancer if eaten, breathed in, or if it somehow enters your blood.)

Howard drove us back to the elevator that would take us back up to the surface - hot and sticky. It would be nice to be out of here.

Parts 7 and 8