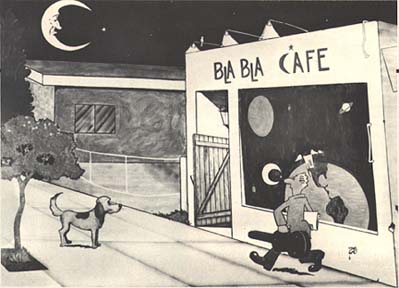

The BLA - BLA CAFE in Studio City: This was the plece, THE PLACE, 1960s - 1970s.

As Peace Wilson portrays it in chapter 18, Studio City and the focus of the 1980's "bohemia" has changed. But of course, that is the nature of the phenomena characterized by that elusive name. The times change often more quickly and always more easily than the people to whom the changes are happening. That was, after all, the lesson of Shakespeare's character Falstaff. The San Fernando Valley and its Studio City, in that sense, are no different than the England of the Henrys IV and V. None of which should come as any surprise . . .to historians.

By the 1980's, the area known as Studio City contained about 45,000 people, and the only studio was the CBS Studio Center, a hundred feet or so north of Ventura Boulevard, inhabiting buildings previously owned and operated by more "historic" owners. Well, no doubt CBS will someday be a "historic" name also. The same will also be said of the place where older people could safely go for walks in the evening . . . remembering when it was a safe, healthy place to raise children.

Looking across the Valley from the hotel balcony, with the assistance of binoculars and a clear day, I can see as far north as the City of San Fernando and the Los Angeles community of Sylmar. San Fernando has been ably described by Jennifer Mitchell in chapter 13; what can be added about Sylmar? The entire northeast part of the San Fernando Valley, and indeed most of the Valley north of Roscoe Boulevard (the original division line between the north and the south halves of the Valley), is a foreign country to those who live south of that line.

Sylmar, Tujunga, Sunland and portions of other northeast communities represent the older Valley, the place to which many of the older inhabitants of Van Nuys, Lankershim (North Hollywood) and other places south of Roscoe Boulevard have been pushed by various newcomers in possession of differing lifestyles as well as more money.

Good old Sylmar—the epicenter of the 1971 earthquake—where the largest olive grove in the world outside of Tunisia once existed, where many of the ancient olive trees still adorn the yards of the small residences as well as the larger mini-ranches. By 1942, much of Sylmar was owned and produce-farmed by American born, citizens of Japanese ancestry (actually about 50% of the farms in Los Angeles County in 1942 were owned by American citizens of Japanese ancestry), who had taken over the declining olive orchards.

Throughout the Valley in 1942, over 1,000 of these Americans—owning over 80 small farms as well as other businesses—were deported to "relocation camps, " such as the one at Manzanar in Owens Valley. Their property was either simply confiscated or it was purchased by "friendly" neighbors at exceptionally reduced prices. Of course, these people were not sent off to "Arbeit machts Frei" death camps, as were the Jews under Hitler's fascist Germany. But it must be said that one hell of a lot of local people did "real well" as a consequence of the forced sales and of the transition in land ownership. Ah, 40 years later it has all become history . . . yet, as mentioned earlier in this book, remembering is what Clio and history are all about.

The relatively lower prices for land in that corner of the Valley means that its "frontier" status will not long remain. Indeed, in 1981, over 1,000 newly constructed condominiums will be: available for purchase, lending institutions and interest rates permitting. Newly constructed freeways have tied that little reminder of the old days into the Valley-wide freeway network, and thus until the traffic increases it is now but a few minutes from the center of the Valley.

At that corner of the Valley, men still get just plain haircuts, go to the American Legion or V.F.W. hall for pinochle once a week, drive American made pick-up trucks and wear non-designer jeans. Their dreams, when they continue to pursue them, include moving out of the Valley into the next valley, into "Canyon Country," and then seceding from Los Angeles County to form their own and independent county. Not only is Los Angeles a most strange, disturbing and far distant place to them, but so also is that part of the Valley that has become another city intrusion into their lives . . . Ventura Boulevard.

At times it is inconceivable to think that this Valley once inspired the words: "Where the West begins;" that Hoot Gibson's nightclub on Ventura Boulevard near Laurel Canyon Boulevard, called the Painted Post, advertised itself as "the place where the pavement ends and the West begins." Laurel Canyon, in those days of post-prohibition, was paved all the way over the Santa Monica Mountains from Hollywood into the San Fernando Valley. That pavement ended just beyond Ventura Boulevard, and Laurel Canyon almost disappeared, in the opinion of many from the city side of the hills, into "dirt, dust, and walnut groves." But it was that very "dust, dirt, and walnut groves" that attracted the thousands . . . the hundreds of thousands who came to "Make the San Fernando Valley my home" at the conclusion of the Second World War.

II

Oh! I'm packin ' my grip

And I'm leavin' today,

Cause I'm takin'a trip

California way.

I'm gonna settle down and never more roam

And make the SAN FERNANDO VALLE Y

my home.

I'll forget my sins,

I'll be makin' new friends

Where the West begins

And the sunset ends,

Cause I've decided where "yours truly"

should be

And it's the SAN FERNANDO VALLEY for me.

—1943. Gorden Jenkins.

Historically, and in particular regard to the San Fernando Valley, the wild and primitive fell before the invaders and carriers of the pastoral. Within an even shorter period of time, the pastoral became purchased and planted to grain; the grain fields quickly disappeared under the pressure of development, and numerous small farms, ranches and townsites sprang up on the Valley floor. History has a way of moving ever more quickly the closer it appears to our own time, and the farms, ranches and small towns were mostly obliterated by the rush to suburbanize, to "sluburbanize," as some called it even back then. And by the 1980's, the Valley was a city . . to many, practically overnight. But they had been the sleepers.

Sitting up here I am reminded of Raymond Chandler's 1947 description of a drive from Hollywood through the Valley along Ventura Boulevard:

I drove east on Sunset but I didn't go home. At La Brea I turned North and swung over to

Highland, out over Cahuenga Pass and down on to Ventura Boulevard, past Studio City and Sherman Oaks and Encino. There was nothing lonely about the trip. There never is on that road. Fast boys in stripped-down Fords shot in and out of the traffic streams, missing fenders by a sixteenth of an inch, but somehow always missing them. Tired men in dusty coupes and sedans winced and tightened their grip on the wheel and ploughed on north and west towards home and dinner, an evening with the sports page, the blatting of the radio, the whining of their spoiled children and the gabble of their silly wives. I drove on past the gaudy neons and the false fronts behind them, the sleazy hamburger joints that look like palaces under the colours, the circular drive-ins as gay as circuses with the chipper hard-eyed car-hops, the brilliant counters, and the sweaty greasy kitchens that would have poisoned a toad. Great double trucks rumbled down over Sepulveda from Wilmington and San Pedro and crossed towards the Ridge Route, starting up in low low from the traffic lights with a growl of lions in the zoo.

Behind Encino an occasional light winked from the hills through thick trees. The homes of screen stars. Screen stars, phooey. The veterans of a thousand beds. Hold it Marlowe, you're not human tonight.

In 1947, after Encino, even the cynical Marlowe found nothing until he reached the small town of Thousand Oaks where he stopped for coffee, before cutting over to the ocean and returning to Los Angeles via Malibu. Of course Marlowe was a private investigator, not a historian. Yet he had driven along the southern edge of an area as large as Chicago and inhabited by over 300,000 people, 99% of whom—as the boosters boasted— were "white" and Anglo. Marlowe may have been, by his own statement, "not human" that night; clearly, he was also not involved in real estate.

During the Second World War, hundreds of thousands of Americans had relocated to southern California to work in the aircraft and ship building industries; other hundreds of thousands, as military personnel, had passed through the region, getting a taste for the sunny and snowless life. When the war ended, the United States government's programs of educational and housing assistance to veterans encouraged many of those to stay in southern California and others to move here. In addition to the sunshine, the absence of rain and snow, low housing and transportation costs attracted hundreds of thousands of people to buy and live in the Valley in the 20 years following the Second World War. From less than 200,000 before the War, the population soared to 400,000 in 1950, over 700,000 in 1960, reaching one million by the mid-1960's.

Once housing construction resumed after the war, a veteran could purchase a new two-bedroom home for $10 down and $50 a month. Regular gasoline at an economy Haines Brothers station at the top of Cahuenga Pass sold for 10.9 cents a gallon, and a 1946 Ford Deluxe Sedan could be purchased for $1,131; a Chevrolet Fleetmaster, for $1,076; a Packard 6, for $1,624; and a Cadillac, for just under $2,000.

But the times changed, as they always do, and prices began to rise. The average priced newly constructed home that had sold at $9,000 in 1949 could be re-sold for nearly $15,000 in 1955. Still, that was not excessive and required a combined family income of around $6,000 a year. Valley incomes were still a bit higher than the national average, and basic living costs were still considerably lower. Regular gasoline did not exceed 25 cents a gallon until 1967, for example. But costs for housing, for the land, building materials and labor continued to increase.

By 1960, the average market value of a San Fernando Valley home reached $18,850. Still, that was an average, and many homes could be purchased for considerably less, as well as higher. The average working person's income in the Valley in 1960 reached $8,011, still $11 above the amount required to qualify for purchase of the average priced home. While clearly the times were "a'changing," an average family with one person earning that average income could still purchase that average priced home of their own.

From the end of the Second World War to the end of the 1970's, the size of that average house increased by 100%, from 850 square feet in 1948 to about 1,700 square feet in 1980. In plain English, the two bedroom and one bath home of the immediate post-war years grew to the four-bedroom-and-two-bath home of the late 1970's. Prices also increased. By 1973, a local city planner observed that "few single-family houses can be built for less than $35,000."

In little more than a decade, housing costs had doubled—as had interest rates on the mortgages, and therefore, the monthly payment. By the late 1960's and certainly by the early 1970's, the San Fernando Valley had lost its housing cost advantage relative to the rest of the United States—and during the same period, real incomes received by the average San Fernando Valley person also declined to near the national norms.

The surplus that helped make the Valley the land of dreams come true was not only gone, but the economic process quickly reversed itself. Too soon, San Fernando Valley homes were being priced well above the national average. By the late 1970s, the average price of a home selling in the Valley reached $110,000, a price that required a combined family income in excess of $45,000 a year and monthly payments of $1,200.

III

men's palms, no more,Inside a cave in a narrow canyon near Tassajara

The vault of rock is painted with hands,

A multitude of hands in the twilight, a cloud

of

No other picture. There's no one to say

Whether the brown shy quiet people who are

dead intended

Religion or magic, or made their tracings

In the idleness of art; but over the division of

the years these careful

Signs-manual are now like a sealed message

Saying: "Look:we also were human; we had

hands, not paws. All hail

You cleverer hands, our supplanters

In the beautiful country; enjoy her a season, her

beauty, and come down

And be supplanted; for you also are human

--- "Hands. " Robinson Jeffers.

The generation that was born here in the Valley after the Second World War probably from 1947 to 1957 to maybe 1960 is a very interesting group, very peculiar. To begin with, that generation of people is the first generation of Americans born and raised in a suburb. They are the first products of an American phenomenon: suburbia. There are other suburbs in other places, but few of them came into the full bloom of vigor until the late 50's, the 60's or 70's.

The suburbanization of the San Fernando Valley got started early enough so that by 1946 to 1948, all those Gl's who wanted to could settle in a place where life was easier. To live in California, to live in southern California, to live in Los Angeles, to live in the San Fernando Valley may sound ridiculous to many today, standing up here and looking down at it from almost where Charles Maclay in 1873 viewed it all. It's almost incomprehensible.

But only almost. The weather; the winters are hard back East. The struggle is always the same. One's chances of improvement based upon the experiences of the 30s and the war years left little doubt that opportunity lay westward. That opportunity did in fact lie westward. Housing costs, land costs, living costs, all of the essentials were in fact cheaper here. Cheaper construction, perhaps, but then the weather was nice and warm. Fewer winter clothes to buy, less fuel bills to pay. Certainly lower ones. There was room. There were still fields and orchards. The air was still clear. You could own a house here instead of renting an apartment in Chicago or Des Moines, fighting the weather. Here was sun, health, wealth and happiness on a budget. That's the secret, the budget.

Average incomes were in fact a bit higher here, but not that much relative to from whence they came, and not enough to explain the immense leap in their material standard of living. It was that the basic costs, the essential costs were so much lower, one had a surplus. Of course, it was not necessary for the wives to work to support the mortgage payment, the car payment, even the private school payment for those who sent their kids to private schools. Other costs being minimized, there was that surplus.

That's the key—it's that surplus which provided the economic environment, the cultural, the social and the emotional environments. It is that surplus which allowed those parents to raise their children with quantitative and economic expectations that now, beginning in the 1970's ' and into the 1980's, the society cannot fulfill. And what happened is that a generation of young people was raised here whose expectations about life cannot be realized. They were unrealistic expectations in the first place; mostly, they were the product of a series of historic accidents

The booming prosperity of America following, the war, with large profits resulting from the devastation of all our competitors, with our almost unlimited world power, even, mind you, with our, power to spread the fear of nuclear war. Now we have a 15-year spread of people aged 21 to 36, products of this environment, of the San Fernando Valley, raised in suburbia, where father's salary alone was enough. Where one lived in one's own home; where one came to expect not simply enough but a surplus. And folks, it ain't here any more. The surplus is gone; the expectations linger, and that may be the explanation of the kind of frantic searching that goes on by so many of these middle class young people.

Too sophisticated for the old time religions to work, they turn to the "new time religions"—to the transcendental meditationists, the Werner Ehrhards, the WMI. Through all the self-actualization and all of the encounter groups, they are searching for a reason. Not for being, but rather for a reason why they are not successful. Why they can't even match the relative economic carefreeness of their parents. Had they been born and raised working class, honestly lower middle class, those expectations, those aspirations would not have been so implanted in them. But given the essential secularity of this society, given the fundamental self-orientation of this society in terms of meeting and matching oneself to the expectations that have been implanted as well as the expectations of the peer group with whom they have grown up, they measure their own worth as human beings in terms of their ability to "succeed."

This manner in which they were raised has put the onus of failure to match their expectations upon themselves. They blame themselves. Few of us recognize or understand the circumstances that come together to form an environment, a milieu in which one is raised and from which one draws certain fundamental ideas about life, certain values, certain attitudes. There is a huge difference between wanting and working towards an improved standard of living, and being raised to expect it.

From these unrealistic expectations held by all those people—the ease of acquisition with the promise of more tomorrow—has come one vast emotional, psychological, and spiritual redundancy. They can't cope with what has become of their lives and whether it is lack of sophistication, experience or something else, they seem unable to get outside themselves and see that the failure is inherent in the system itself; the failure is not in them.

Guess who the parents were of the "me generation"? Those pretty "white Anglo" young women picking oranges off of trees outside their homes. Those are the mothers and the fathers, the ones who thought they were escaping the bondage of the past; who had put in their time in the war; who had the Gl Bill and the Gl loans for homes; who really expected that they were going to have a better and newer way of life in the here and now. Standing around their swimming pools, the men admiring their pretty young wives, their pretty children, entertaining others just like themselves.

Those pretty children for whom they wanted to do so much and for whom unwittingly they did too much; all those men standing there, congratulating themselves. Had they congratulated themselves on being the recipients of good luck, of a series of fortuitous circumstances; had they recognized their situation realistically and had in a sense thanked the gods rather than taking credit for it all themselves, they and their pretty wives might have raised a different generation of children, of young people.

The song is gone; the melody lingers on. It was a temporary, a very temporary interlude. And these poor young people are the products of that fantasy. Is it any wonder then, being products of one fantasy and unable to realize or match it, that these people would be so pathetically and so unhappily susceptible to other fantasies, to other illusions, and to the various psycho-spiritual messiahs and politicians who know how to manipulate the symbolic representations of their frustrations, their anxieties, their doubts of their self worth, their fears of everything?

Obviously, if one convinces oneself or believes for some reason or another that they are responsible for their fortunate circumstances, for the opportunities to pick oranges off trees just outside the door; for the opportunities to mingle with others of their sort around swimming pools, and barbecues, when that level can no longer be maintained, then they must also accept the blame.

And the young, who themselves knew no other existence before the better and newer way of life here and now, that grew up expecting an even better, an ever newer way of life for their here and now, must be the most unfortunate people of all. Diversions abound. But those diversions cost money and each day they cost more and more money. Consumerism, faddish, hip-happenings require an ever increasing level of income or, which is more than likely, the burden of an ever increasing debt. A debt brought about by the need to prove that this is a better and newer way of life here and now and to prove it in the only way that they have ever learned, quantitatively. Good God, think of the anxiety, think of the fear that must run through their lives. No wonder they are so depressed and so adamantly opposed to hearing, to listening, to reading what they call downers or "bummers. "

IV

June 19, 1981.

We buried my father five years ago today, four months after my 16th birthday. Since, this date has provoked in me a philosophizing about the past, present and future. I often wonder, and not only on the anniversary of his death, why he decided to end his life in suicide. Apart from other reasons that I have guessed at, I believe he failed to find the security and to realize the dreams that he had pursued and desired throughout his life; the dreams which had brought him to the Valley.

A lover of nature, he was raised in the city and eventually moved to the Valley in 1961. Back then, although I barely remember, there were still vestiges of the orange, walnut and olive groves that had once dominated the Valley floor. But grassy vacant lots and productive fruit groves were increasingly displaced by apartment complexes and shopping centers. My father watched the change of a pleasant suburban area into an increasingly congested and polluted urban one. Through the eyes of a man who loved nature, how that change must have polluted his spirit as well as his body!

Now I, like my father before me, watch the changes continue to occur; changes which symbolize for me the loss of that security l had grown up with. As a kid, I remember believing—of somehow being certain—that the world was a good place, that everything was being taken care of in the right way; a way which was to the benefit of humankind as well as to the earth itself.

Children are innocent, and how lucky they are! The shattering of my own comfortable belief began during a lecture on topsoil erosion in a sixth grade classroom. We were told how many inches of soil there should be in certain fertile areas, and how many inches of productive topsoil were left. How clearly I remember the ominous way in which she said, "Once that is gone, life as we know it will also be gone. "

Suddenly the trees on my quiet street were no longer there just for our childhood climbing, nor was the grass just a mat for our cartwheels. As if to reinforce my loss of innocence, our neighbors felled a spectacular hundred-year-old pine that grew in their backyard; a tree so huge that from any elevated point in the Valley, one could see it rising above the houses—a proud monument to life.

I walked out of the house that day and saw my father sitting on the porch, smoking and staring across the street at the now vacant spot. Something essential was missing. "They chopped down the tree! " I cried. He simply nodded, and in his silence I could sense the sadness he felt. I felt the same sadness—and also anger—but I was only a child. He was an adult, a man who, no doubt, had seen many trees destroyed, many open spaces asphalted, many hillsides carved. I began to despise the concrete that plastered the earth and immobilized all natural growth.

My father had come to the Valley for quietude on the periphery of a city that instead continued to expand, filling up with people whose lives had no room for aesthetic beauty and who had no comprehension of the essential functions of nature.

In his last years, he talked of moving to Alaska. I suppose he realized that even Alaska is not too immense to be consumed by an ever-expanding, grabbing way of life. For a man who intensely loved and respected nature, who had grown up in the city and found it odious, perhaps his decision was to see no more of the wasteful destruction that characterizes the worst of America.

My father chose the Valley as a final stepping stone, a place in which to raise his children in an atmosphere of security and peace. As his child, I am leaving this place that has become one of increasing crime, noise and pollution. Where to now? It is difficult for me to think of a place that is not on the periphery of a city or one not destined to become a place of noise and pollution.

Well, perhaps Alaska. —Catherine Billey

Kurt Sechooler pointed out in chapter 14 (as well as in his most original full-length study, The Next Ten Years: The History of the 1980's Before It Happens) that these products of the post Second World War baby boom have now reached maturity. They are increasingly demanding a voice in the national and local decision-making processes, business as well as political. They also desire their share of the "good life." As even the briefest encounter with the demographics demonstrates, their numbers are huge. The age of the group currently in power is so far advanced that by the end of the 1980's—if not sooner—these young people, born between 1945 and 1960, will constitute the leadership in business and government, at the national and the local level. It matters little how those currently in power would have it, their days are limited by the demographics. A small, in-between group in the population, the Depression-born, numbered too few to successfully impact the society.

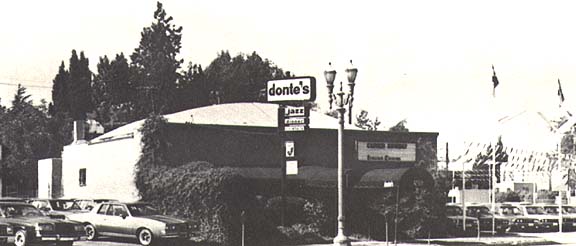

Dante's jazz and Supper Club, on Lankershim Blvd in North Hollywood, kept jazz in the Valley through all the in between and the many lean years.

As one of the group long known as the "silent generation," though some of us have been less silent than others, I realize how little impact we have hand upon national and local policy. In practically every one of the so-called developed nations of the world, from the Soviet Union and its East European allies, to the United States, Western Germany, Japan, Great Britain and their respective ideological supporters, the leadership —male or female, though obviously and conspicuously predominantly the former—are all over 50 years of age. In some of those countries, the leadership group's age is in the 70's and 80's. Only the most dense could continue to believe that they will live forever, independent of the quality of the leadership they have already exercised. As apparently in the case of the dialectic, there are some things on this planet that no amount of personal wealth, power and prestige can alter, change or avoid. Our children are never as we are or were; good for them. And our grandchildren, even less so . . . fortunately for whatever chance this Valley has to survive as a viably livable place.

By 1981, the oldest of that poet-war group had reached 36 years of age; the youngest, about 21. That group represents the future, regardless of what those who are older might wish. Certain customs, mores, institutions and laws tend to perpetuate the tradition of the dead governing the living. And most of the nations of the world suffer from that dysfunctional tradition. Yet most of those nations—Poland for a most contemporary example, the Soviet Union, the United States, and others, in a few years—will necessarily witness the confrontation of one generation succeeding another. As they used to say in England, "The King is dead, long live the King." Since the generation born in the decade following the First World War will reach the end of its string in the 1980's, what sort of people will constitute the new royalty, and what has all of this got to do with the San Fernando Valley?

The end of the petroleum era and that period of low energy costs ought not to obstruct the young people's plans for the future. In the late 1970's, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena published an energy conservation study that indicated that using solar energy and only one-half of the roof space in the San Fernando Valley, well over 100% of the then current business and residential demand could easily be achieved. Clearly, most of the problems, particularly the smog, can he dealt with by those who have the necessary psychological ability to "break with the past." Those young people, who in 1981 range in ages from 21 to 36, will soon be taking over the San Fernando Valley—as well as the rest of the United States and the developed nations. From that inevitability there is no escape. And thus the point of this lengthy and digressive discourse, who are these kids? Better yet, who are our children . . . what is our future, for if there be a future, it will be in their hands, springing from their minds. Just exactly what sort of a world did the San Fernando Valley, particularly between the years of 1945 to 1960, present to those who will shortly be the leaders, if they stay in the Valley? It all sort of naturally follows that the contemporary versions of the uplifters and the positive thinkers are in fact so popular in a place built by the boosters and the boomers, where any suggestion of the fragility of it all was considered subversive. Such an artificial world, a desert transformed by importation of water from hundreds of miles away. To be paid for by those whose water it had been, to he paid for by future generations through bonds, keeping electrical rates lower than any place in the nation, subsidized by taxpayers elsewhere, by bonds that you pay off later, by environmental degradations, that if we are lucky, will be paid off sooner rather than later.

Something fundamentally unreal about it. Planned and platted and subdivided by mountebanks. Peopled by believers who did not see how transiently lucky they were. A place without substance where creativity is measured in terms of industries devoted to fantasy, diversion and vicarious experiences. Check out a jazz song, the lyrics of which go, "We've got to figure out a way to save the children, for soon, it will be their turn to try to save the world."

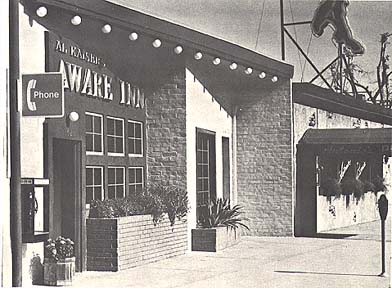

Sinece 1960, the Aware Inn has been a favored island of quality for lunch or dinner over ideas, scripts, manuscripts, and most especially for those times that lovers and other romantics apparently require.

Rolled out on some specimen board

floured, notable in relief's shadowings

as some archaic principle . . .

We never, did you notice? Discuss

the rights of territory, and

finally we ended up as hostile,

chest-pounding apes

over-excited, protecting domains

intruded.

Trust in no one, the genes said,

when guarding your boundaries,

but family.

Did we then not regard each other

as kin? Was the mistake,

from the start, that we claimed

separate tribes? Allegiance

justly pledged, by rights and by history,

we did not sign in blood, but in water

we must have preferred.

Flexibility of purpose, you know.

Flexibility of option, you remember? In water.

We dwell in different parts of the jungle, I am afraid.

And I am afraid, justly so.

My family has grown no larger,

grows smaller with the passing of

time&members, grows smaller and

cannot protect its territory as in

time of greater numbers.

The boundaries are closing in,

and I look for blood-brothers . . .

—Deborah A. Smith

22/ VIEW FROM THE 17TH FLOOR

Lawrence C. Jorgensen 1981

I

Cain knew his wife, and she conceived and bore Enoch;

and he built a city, and called the name of the city after

the name of his Son, Enoch. --- Genesis. 4:17

From before the Book of Genesis to Ortega y Gasset's Naturmensch, through Jefferson, Hawthorne, Melville, Faulkner, Abbey and Jorgensen, a "soft veil of nostalgia," as Leo Marx in his The Machine in the Garden described it, "hangs over our urbanized landscape. . . largely a vestige of the once dominant image of an undeviled, green republic, a quiet land of forests, villages, and farms dedicated to the pursuit of happiness." Ah, there can no longer be any question that from the most ancient times to the present, the emergence of the city with its necessary destruction of a rural and pastoral or in more modern times a suburban way of life and living has caused much cultural and psychological anguish. The Hebrew holy books and the even more ancient Hindu texts all record a progressive fall of humankind in terms of its increasing urbanization. Independent of the social, cultural and intellectual amenities proferred by the city, something fundamental within the human spirit, particularly the American and most particularly the western American, rebels against the inroads of concrete and cemented living.

Still, although we are primarily a people who have fled the small and the rustic, the nosey, sterile and too often constricting small town, village or shtetl—as the case may be—as our flight progresses, we continue to seek river and beach; fronts, homes up against the hills, acreage with room " to grow. "

Even the advertising industry assumes, which each of us can easily validate at any moment of the day, that the selling of their wares is enhanced by the association of the beer, the cigarettes, the perfumes, the automobiles, the clothes, women and men themselves, with what they consider "nature." With sex continuing as a dominant theme, the most successful advertisements play both: sexy people, preferably women of course, parading the wares of the sponsor next to a mountain stream, along a beach, in the desert or under a forest canopy.

fog where the moon Falls on the west.Before the first man

Here were the stones, the ocean, the cypresses,

And the pallid region in the stone-rough dome

of

Here is reality. The other is a spectral episode:

after the inquisitive animal's

Amusements are quiet: the dark glory.

--- "Hooded Night. " Robinson Jeffers.

Atop a low hill, standing guard where the Hollywood Freeway spills over Cahuenga Pass into the Valley, stands the 20-story Sheraton Universal Hotel. Actually, the 500 room luxury hotel has only 19 floors, since the number 13 is skipped, as is true in most multi-storied buildings in the United States, not that we are a superstitious people. Consequently, "The View from the 17th Floor" is really from the 16th. Well, things are often not as they first appear.

From the 17th floor, l can look down and west along Ventura Boulevard into Studio City where Mack Bennett of the Keystone Kops produced movies in the late 1920's. Soon after, the clear air attracted Republic Motion Pictures, and by the 1930's, 18,000 people lived in the immediate area. Republic produced hundreds of westerns, starring William S. Hart, Hoot Gibson, Roy Rogers, John Wayne, and others of legendary fame. The San Fernando Valley also starred in most of these movies as "the West," wherein the "western" action took place—especially in the Chatsworth area and the Santa Susanna Mountains.

Growing up in the area during the late 1940's and early 1950's, Studio City was a magical land to many. In addition to the movies being made right there, actors such as Errol Flynn walked the streets along with countless others, especially the Hollywood cowboys. Indeed, a large number of the residents kept their own horses, and there was still space in the Santa Monica Mountains in which to ride. It was an area where older people could go for walks at night; it was a safe, healthy place to raise children.

|

Considered by many to be the "prize of the Valley," Studio City, apparently, was fated from its inception to become the Valley's closest approximation to a "bohemian" neighborhood, certainly an area that attracted musicians, writers, movie-hopefuls, and other artists . . . some successes and others from among the countless "would be's." Roy Rogers (Leonard Slye), for one example, moved to the Valley in 1936 while still working with a group known as the Sons of the Pioneers.

He was the first to record the Gordon Jenkins song, "San Fernando Valley" in a 1943 movie by the same name, though it was Bing Crosby's recording in the same year that made the song and the Valley nationally famous. Living at the comer of Ethel and Oxnard Streets in Van Nuys, Rogers could see acres of "bean fields, alfalfa and orchards." He also once remarked that "most of the musicians we knew wound up living in the Valley, because homes were so reasonably priced." But movie stardom soon enabled him to move, as so many have since, into the hills above Sherman Oaks, south of Ventura Boulevard.