20/The Desert Sink: Water for the Southland

By Lawrence C. Jorgensen, 1982

Southern California is a beautiful land in autumn. Nature seems to be dreaming.... But under the dreamy peace of this scene is concealed a dreadful secret—Nature is suffering for water. Men or animals cannot wander far from the known springs and water courses, for the thirsty air drinks the moisture out of their very blood, and if they cannot get water, they perish, just as the vessel that has boiled dry speedily goes to pieces. —Edward R. Howell, 1894.

In a sense, the history of Southern California is the record of its eternal quest for water, and more water, and still more water. —Carey McWilliams, 1946.

I

Just as certainly as a people cannot escape their history, history cannot escape the ecosystem within which it unfolds. Climate and weather, precipitation and fresh water supplies, land fertility and the resource lease of the particular civilization in general all combine to define and to impose material and consumption limits only recently becoming clear.

Humankind's record is mostly a record of the success or failure of various civilizations' accommodations to their respective ecological niches, the available resources of their particular place. The San Fernando Valley, clearly, is semi-arid, or semi-desert, at best. An arid biome, or desert, is usually defined as a place of low moisture because of low precipitation, generally less than 10 inches of rain a year. A semi-arid, or semi-desert, is a region that receives over 10 inches but less than 20 inches a year.

Average rainfall in southern California varies from about 6.5 inches around Bakersfield in the southern San Joaquin Valley, 10.4 in San Diego, 2.3 at Brawley in the Imperial Valley, to 14.8 for the Los Angeles Basin. The Santa Monica and the San Gabriel Mountains screen out some of the basin’s local rainfall, so that the San Fernando Valley receives less than the basin as a whole. By way of contrast, Fort Bragg, along the coast and about 150 miles north of San Francisco, averages about 38 inches a year.

According to studies of tree-ring data, long periods of low rainfall—drought, even—have been the norm for the past 175 years. And within these periods, four short but wet cycles have raised the local long-range average to over 14 inches. Other studies of even older data suggest that the past 175 years have actually been wetter than what is "normal" over a longer period of time. Well, let them argue. What remains clear from both is the arid and semi-arid nature of the region. Thus, to talk of the San Fernando Valley, its past, its present or its future without considering something as fundamental as the continued availability of fresh water is not only foolish and naive, but it is dangerous for present and future planning.

When we choose to live and work in an area that is a desert or nearly desert in its character, we had letter learn to understand the ecology, the economics and the politics of water. It does little good to agonize over petroleum shortages, or the high price of gasoline and heating oil when they are available, if there is no fresh water. Understandably, as urban dwellers we are so far removed from a daily confrontation with the ecosystem of which we are an integral part that we have lost touch with much that is essential to our physical survival.

Coming mostly from places in the United States, or in the world, where water shortages are unknown, and emerging from a historical period during which energy costs were incidental, we have been poorly prepared for the rapidly approaching future. To most of us in the city, water is something that comes out of a tap, somewhat similar to the notion that milk is something that comes out of a carton. There is very little understanding of the highly complex system of delivery required to put the water under pressure at the tap. We call a plumber when the water fails . . . it is somehow or the other a plumbing problem . . . and then we complain about the cost.

How does water get to the tenth floor of a multi-storied building, or to the twentieth, or how does it get over a mountain are questions we rarely ask. And even less do we inquire into the source of that water and the amount of energy its delivery requires—for it will not flow uphill by itself.

One writer in the later 1940's, Carey McWilliams (California: The Great Exception) touched upon the social-psychological problem that helps create the "contradiction" so fundamental to most of southern California. The water problem in Southern California is in part sociological and cultural: people do not understand the importance of water. It would be most unfair, however, to censure these people, for the scarcity of water in most Southern California communities is a closely guarded secret [emphasis mine).

Along with fresh air, fresh water is a unique and finite resource. There is no substitute for either one, whereas solar energy for example, can be substituted for vanishing fossil fuels. The decreasing air quality in the Valley is readily visible, and the official data is even less encouraging. As measured on an official scale from good to hazardous, the Los Angeles Basin registered good only about 40 days out of the 365 of 1980, with the more atmospherically confined San Fernando Valley doing even less well on that scale.

Well, perhaps humans will learn to adapt and to survive with air that is less than good. And perhaps our real estate and political leaders are correct in their assertion that air quality is actually improving . . . or that air pollution is caused mostly by trees, shrubs and other forms of vegetation. It is difficult, however, to be as cynically optimistic about a lack of fresh water.

National and global in extent, there is growing awareness of the essential fragility of the ecosystem and of the weakness inherent in any political-economic system which neglects the consideration of that most finite and unique of all natural resources. This consciousness is beginning to slowly percolate down from the experts into the consciousness of the larger body of citizens still concerned about something called a future.

In the United States in 1900, fresh water use averaged about 600 gallons a day for each person. By 1980, the consumption had risen to over 1800 gallons a day for each person. That 300% increase in average daily consumption generally reflects the overall increase in consumption of all resources.

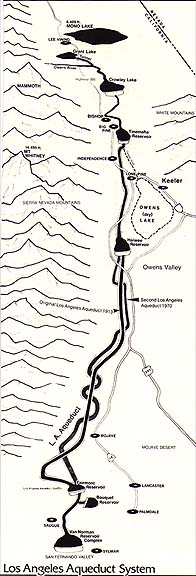

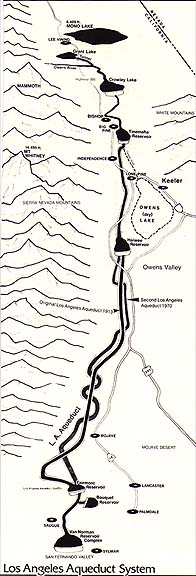

Two-thirds of the rain and snow that yearly descends upon California falls in the northern one-third of the state. But as most of the state's population and the extremely water intensive and valuable agricultural industry lie mainly within the southern one-third, getting the water from the one place to the other has been, as it continues to be, a most complicated ecological, economic and political juggling act. In addition to the pumping of ground water, southern California depends for its supply of water on three aqueduct systems, the Los Angeles-Owns Valley, the Colorado River and the California—three long and narrow man-made rivers.

While there is a small mixing from the various sources, practically all of the water in the pipes in the San Fernando Valley comes down from Owens Valley and the Mono Lake Basin. Actually, the Los Angeles-Owens Valley Aqueduct provides much more water than is consumed in the San Fernando Valley. That "slim 338-mile lifeline, " as the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power's general manager called it in 1976, supplies about 80% of the total water needs for the entire city of Los Angeles. Obviously Los Angeles continues to have a vital interest in the politics of those two northern counties, Inyo and Mono.

A spreading basin in the northeast part of the Valley awaits the winter rains, as the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power struggles to replenish the every diminishing ground water.

II

"It never rains in southern California, " runs a refrain in a recently popular song. While those lyrics originally intended cynicism and sarcasm, taken literally, they are pretty close to the truth. Indeed, with 45% of the state's population, Los Angeles receives a mere 2% of all the precipitation that falls on the entire state in any "average" year. Officially, the long-range "average" rainfall in the Los Angeles Basin is between 14 and 16 inches a year.

And for various reasons, when the winter rains do come to the southland, including the runoff from the snows in the neighboring San Gabriel Mountains, most of the water is flood-controlled and channeled through the city and out into the ocean. A small percentage is captured and stored, either behind rapidly silting dams in the San Gabriels, or run into settling basins to percolate into the ground. That water—that recharging of the ground water reservoir—is available for pumping at The Narrows. Almost 15% of the total supply of water for Los Angeles comes out of that underground reservoir.

Water in the ground in the San Fernando Valley once was so plentiful and so pressurized that shallow holes in the ground produced energy-free water called artesian wells. Until court action by the city of Los Angeles stopped Valley farmers from pumping, they reached artesian water at a mere 40 feet. It was those free-flowing wells that originally transformed the desert that is southern California, the San Fernando Valley, into a garden and showplace to eastern land buyers by 1900. Those early developers, owners of small ranches, farms or orchards knew little to nothing of water shortages. How could they? What does someone from the ample rained regions of "back east" know of drought or dry cycles?

In 1900, the Los Angeles Basin had wells producing some 78 million gallons, enough for a population of 500,000 people. Los Angeles' population at that time was about 150,000, so there was more than enough water for the present without overdrawing the "bank," without taking more out of the underground reservoirs than was annually being replenished through rainfall and the natural recharging of the water bank.

On the eve of the Second World War and the precipitous growth of southern California, all of the artesian wells had long since stopped sending their energy-free water up onto the surface. The water table had dropped and with that lowering, the pressure had also dropped. In 1941, some 30,000 pumps were in use in southern California, tapping—draining—the underground waters. Wells go deeper and deeper as the necessity arises; beyond a certain depth, mechanically driven pumps have to be used to tap the reservoir. In 1941, the wells in Pasadena, just to the east of the Valley, were down to 350 feet . . . and dropping.

By the early 1980's, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power possessed some 95 wells in the San Fernando Valley. At any given time, about 80, with some as deep as 1,000 feet, were drawing water from the underground reservoir that was both legally and actually the Los Angeles River. As was generally true state-wide, the amount of water being drawn out of the ground greatly exceeded the amount being recharged. According to the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, the "safe yield" from the Valley reservoir approximates 82,000 acre feet a year, though that assumes one of those mythical "normal" years of 14 to 16 inches of precipitation. During the "drought" years of 1975 to 1977, the yield reached 140,000 acre feet a year, nearly twice what is considered " safe. " An " acre foot of water" is the amount of water it takes to cover 1 acre with 1 foot of water, approximately 326,000 gallons.

Mining of the ground water reached a level during the 1970's that finally alarmed the generally complacent leaders of the state. For statewide, in that decade alone, the yearly overdraft was 3 million acre feet; in 1977, a "drought" year, the figure was an estimated 15 million acre feet. In that year, the amount of ground water throughout the state estimated to be both retrievable at any cost and usable was 140 million acre feet. Thus, over 10% of the water accumulated in the ground over thousands of past years was used up in that one year. And for the entire 10 year period, 42 million acre feet had been mined.

A wise capitalist lives off the dividends and the interest which the capital earns, not off of the capital itself. Of course, if that capital belongs to others, such as the people or some possibility called posterity, then apparently it becomes permissible to dip into the capital account. But even that practice, independent of any moral and ethical considerations, soon conflicts with the most elementary fact of a depleted capital or bank account. At that point, the game ends, and the typical embezzler flees to some extradition-free country. In the case of the depletion of a natural resource, it is generally enough to move the operation to another part of the United States. Often it suffices to simply relocate to a different area within the same state.

And yet, even that process can not go on forever; for unlike the proverbial "one born every minute," finite resources—in this case, ground water—are indeed finite. When the ground water is gone, it is gone. And long before the inevitable consequence of a policy of continual overdrafting occurs, the energy costs of mining and lifting from the constantly deeper levels will price that water out of all but the most lucrative markets.

III

The completion of the Los Angeles-Owens Valley Aqueduct in 1913 ushered in a period of rapid growth in agricultural use based upon irrigation in the San Fernando Valley (See Chapters 10, 11 and 12). From 1914 to 1917, the number of irrigated acres soared from 3,000 to nearly 75,000. The dry cycle returned in the early 1920's, alarming many of the city's and Valley's leaders that the total demand for water might exceed the total supply by 1940.

In 1930, Los Angeles taxpayers voted another 38 million dollar bond issue to extend the existing aqueduct farther north into Mono County, to trap and collect the water that normally flowed off the Sierras into Mono Lake. That extension was completed in 1940, in time for the even greater population and real estate boom precipitated by the Second World War. Enthusiasm for the extension into Mono County had been spurred by still another dry period in the early 1930's, seeming to prove the necessity for the expansion of Los Angeles' water imperialism.

A 100-million-dollar second Los Angeles Aqueduct was begun in 1964 and completed in 1970. Once again, a dry period in the early 1960's was used to catalyze the Los Angeles tax and rate payer into voting the necessary bonds. This second aqueduct enables the Los Angeles' Department of Water and Power to increase its export of water from Mono and Inyo Counties by 50%. Specifically, the department diverted four of the five streams flowing into Mono Lake and initiated large scale pumping of ground water from its wells in Owens Valley.

The essential and fundamental contradiction inherent in the entire plan to bring water from the Owens Valley and the Mono Lake Basin continues to plague all of us. As soon as the inevitable dry periods return to the Los Angeles Basin, it is part of the low moisture cycle that occurs in the Sierras. Low winter snow levels in the mountains, which means also little rain in the southland, requires the city to generate more and more water supplies for its ever-increasing urban growth. At precisely the same time that the city needs and demands more and more, the colonies of Mono and Inyo Counties have less and less for export, not to mention for their own needs and wants.

With heavy rains in the southland, that is, with wet years, there are normally heavy snows in the Sierras. Heavy snows in the Sierras, particularly moisture-laden snows (since not all snows are equal in water content per inch of snow), mean large spring runoffs into Owens Valley. Actually the runoff starts as soon as the snow begins to melt, often the day after it has fallen at the lower altitudes, and continues through the summer, as the snow at the higher altitudes melts.

The point of this is simple, I think. At exactly the same time, relative to the continual drought wet cycle, that Owens Valley has plenty of water, so does Los Angeles. The existing aqueduct supplies enough. However, during the drought years, just at the time when the Los Angeles area needs more and more, Owens Valley has less and less to supply. In consequence of this, the city must then pump more and more water out of the ground, thereby lowering the level of the water table in Owens Valley.

Owens Valley farmers, ranchers and others who use irrigation water for their fields, when deprived of runoff water from the Sierras, must pump water up from the ground. The water has to come from somewhere. Ah, but there is the rub. For years, the ground water has been owned by Los Angeles, and each farmer and rancher could only pump as much as the city allowed. And when the city demands more for its own needs, the local users suffer. Apparently, the water can not serve two masters.

Actually, some of the water could serve both. Agricultural water use in the form of irrigation does not actually "use" all of the water that it places into the irrigation ditches, or spreads out onto the land through sprinklers. As much as one-third, sometimes more, depending upon the techniques utilized, of that water finds its way into the ground water supply, thereby becoming available for re-use through more pumping. In that respect, the entire Owens Valley is an underground reservoir, catching and storing both runoff from the mountains, when it is allowed to run onto the valley floor, as well as that portion of the irrigation water not utilized by the plants or lost through evaporation.

A somewhat similar situation occurs in the San Fernando Valley itself, though less today than a few years ago. Water that falls upon the Valley as rain, runoff from the hills and mountains, the watering of lawns, or the still existing irrigation of agricultural lands, all contribute water to the vast reservoir that exists beneath the floor of the San Fernando Valley. For example, the estimates are that as much as 30% of the water people use through their meters for sprinkling and irrigating can be pumped up by the Department of Water and Power, down at The Narrows, and resold to the consumers.

This recharging of the water table, of the ground water reservoir, takes place less as more of the water usage is for industrial and purely residential purposes. As water gets flushed into sewers, drains, sinks and toilets, it is lost to the ground, and shipped out into the ocean. Also, as more and more of the stream beds, the washes and the rivers are paved, less and less of the water normally coursing down them will be able to percolate into the ground beneath and will simply run on out into the ocean. And, of course, as more and more of the surface of the Valley is paved over, as more and more "flood control" projects are installed—designed to prevent water from flooding out onto the ground—channeling that water into sewers and drains, and on out into the ocean, less and less recharging of the water table will occur.

In consequence of this whole series of "technological fixes, " all designed to make urban and industrial living less dependent upon the whims of natural forces, there will be less and less water in the ground. The pumping or recovery of which will require ever deeper and deeper wells, larger and larger pumps and more and more energy to drive those pumps. And as a result, there must be ever higher and higher water and energy costs, for which someone has to pay. More significantly, we continue to develop a greater and greater dependence upon the whims of those same natural forces which, in our collective homocentric arrogance, we are trying to avoid.

Thus, as Los Angeles, and especially the San Fernando Valley, becomes more and more paved over and urbanized, parks and parkways will be squeezed out, and yards and front lawns will be come too expensive a use of the high-priced lands. The inevitable will soon be obvious to all.

IV

More and more water will be needed by more and more people, more and more factories and other businesses, with a parallel decreasing area of land available to catch, percolate and recharge the ground. Sometimes this is defined as a rising demand confronting a diminishing supply; in this case, as with all finite resources, the ever diminishing supply is directly affected by the ever-increasing demand, and at an ever-accelerating rate.

Admittedly, usable water supplies ought not to be a "finite resource," as petroleum or iron ore, but the very nature of the current use of that water precludes its recovery in amounts necessary to balance the demand. Thus, for all practical purposes, fresh water must be defined as a finite resource, and one that is in dangerously dwindling supply relative to the spiraling demand. And as is true with all things in this universe—certainly upon this earth, and particularly in this country— the process cannot go on forever. Question: How much time is there? Specifically, how much water is there available at prices that we can afford . . . and for how much longer?

During the "drought" of 1975-1976, Inyo County successfully litigated a reduction in the amount of water that could be extracted from Owens Valley for delivery to Los Angeles. Also, the state of California cut Los Angeles off completely from the California Aqueduct. To make up for the reduction in water supplies from those two sources, in addition to imposing a minor conservation measure, Los Angeles increased the mining of the ground water from the San Fernando Valley and increased the amount purchased from the Colorado River Aqueduct.

Unlike the Los Angeles-Owens Valley Aqueduct, which generates more electrical power than its operation requires, the delivery of Colorado River water has become very expensive. Nine giant pumps push that water from its diversion point at Lake Havasu along some 242 miles of the main canal to and through the coastal plain of southern California. As energy costs continue to increase, those nine pumps become increasingly costly to operate. Even with the Colorado Aqueduct flowing at 100% capacity during the "drought," however, the extra amount did not compensate for Los Angeles' loss from the cutoff of the California Aqueduct.

Hoover Dam, named for the President who signed the authorizing legislation in 1929, was completed in 1935 under contracts paid for by the United States government. About 155 miles below Hoover Dam and the Lake Mead which that dam creates is Parker Dam, the diversion point for the Colorado River Aqueduct. A regional government agency called the Metropolitan Water District combines most of the local water districts of the six counties of the southern California coastal plain. It is this agency, of which the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power remains the major guiding force, that financed,, constructed, owns and operates the aqueduct.

About one-half of the energy needed to push the water from Lake Havasu to the consumers comes from hydro-electric power generated by the water falling over Parker Dam. The district must purchase the other one-half. Exact costs are difficult to compute. The ways of bureaucracies—national, local, corporate—have become increasingly difficult to monitor by the people who must eventually pay for them. But according to one study of the years from 1929 to 1956, the Metropolitan Water District charged their taxpayers, for the district has the power to tax, 254 million dollars. During that same period, the district charged the users of the water about 30 million dollars—a most generous subsidy from one group within the population to some other one.

V

Contrary to general notions of water use, most city people do not use or consume much water relative to the amount consumed by agriculture and industry. While certain types of agriculture use more water than others, and certain types of industrial production use more than others. Most of the fresh water consumed each year in the United States, and most particularly in southern California—as well as the entire Southwest—is consumed by a system of agriculture that is either primarily or entirely dependent upon irrigation.

The average water consumption in the San Fernando Valley by 1980 was about 120 gallons a day for the one and one-quarter million inhabitants, though the amount will vary with the season and the heat. Nationally, during that same year, it took about 1,000 gallons of water to produce one pound of food. One pound of potatoes required about 23 gallons; a pound of bread, about 135 gallons; a gallon of milk, 930 gallons of water; and a pound of steak, over 2,500 gallons of fresh water. Flushing the toilet requires only 3 to 5 gallons, depending upon the age of the toilet, but producing a ton of steel consumes 60,000 gallons of fresh water. Other residential and industrial amounts of fresh water consumption vary, depending upon the specific activity and the degree of efficiency practiced.

Writers about these matters would prefer not to have to push relatively dry statistics and percentages upon the reader, but unfortunately, some are unavoidable. Southern California residents are too often made the scapegoat by others who seem unwilling to confront the primary issue. The city and suburban people of the San Fernando Valley, of the Los Angeles Basin and of southern California in general are not draining and using up the water of the northern counties or of other states. It is important to realize that of all of the fresh water consumed in the state of California in any given year, about 5%-9% is used by the residential dwellers of the cities, suburbs and towns. Another 5%-6% is used by business and industrial operations, with some obviously using considerably more than others. Nearly 85%—more or less depending upon the region, the crop, and the year—goes to support the state's agricultural industry, the growing of food.

When the inevitable dry cycle returns, city and suburban dwellers are often required to restrict their consumption, to conserve. While conservation is perhaps always a good idea, it is still important to remember that even if all of the state's residential dwellers reduced their water consumption by 50%, that effort would only reduce the overall state use by about 3%. Except for public relations purposes and a sense of communal participation in some public effort, the net state-wide effect of that minuscule reduction must be considered nil.

Well, as you might guess, Benjamin Franklin succinctly summed it all up a long time ago "We learn the value of water when the well runs dry." The well is just about dry; the San Fernando Valley, southern California, the Southwest, the nation—and, indeed, the world—had letter learn the value and the uniqueness of this planet's most finite resource. Ideally, no doubt, every place in the world ought to be self-sufficient at least when it comes to water. The Los Angeles area, of which the San Fernando Valley is a loyal and ecological part, can never guarantee to its inhabitants the necessary water supply that its size requires. Whatever one's political orientation might be, what we have here is a classic example of a "fundamental contradiction." The wells are running dryer and dryer; they are deeker and deeper; the aqueducts become longer and longer; and the natives of the north are getting increasingly restless.

One thing is obvious. The men who control the water

control the future of California. Nothing is more

important to the West than Water. — Raymond Dasmann.Governor Brown Signs $5.1 Billion Peripheral Canal Measure.

— Los Angeles Times. July, 1980.

Inyo County ballot measure proposition passes by a 76% to 24% margin, transferring authority over underground water rights from the City of Los Angeles to Inyo County.

— Los Angeles Times. November, 1980.

Who owns the land is not something trivial to the nation. It is central to our society, to our economy and to our political system. — Paul Taylor.

VI

Occasionally, particularly when the voters are called upon to approve bonds for new construction projects, southern Californians and their legislators are bombarded with warnings of imminent disaster unless they support the boosters and the builders. Mostly, however, serious information and discussion is kept from the transplanted settlers and their native born city and suburban children.

What do they know of deserts, of aquifers and ground water, of aqueducts and water imperialism? How little do they know whom their taxes benefit? And most important of all, to what extent does the prevailing parochialism of southern Californians—perhaps of most Americans and humans generally—obstruct a larger and more ecologically relevant understanding of the magnitude of the stakes?

Water shortages and water pollution, as is true with too many contemporary American problems, are not unique to southern California. Throughout much of the western and southwestern United States, ground water levels are dropping at alarming rates. The nation is unlikely to witness range wars over water rights so reminiscent of a century ago, as the "hired guns" of the 1980's are more likely to be those state and national politicians who have been bought by the various and competing local economic and political interests.

VII

Except for Florida, the 1980 census officially confirmed that the West and Southwest have seen the greatest population increases since 1970. From 1970 to 1980, Arizona grew by 53%; Nevada, by nearly 64%; and California, by about 18%. Practically every large city in the United States that experienced a high population increase during the decade of the 1970's was a western or southwestern city. San Jose, California, jumped 36%, and San Diego became the 8th largest city in the country with an increase of over 24%.

More people obviously means more water consumption, and remember that most of the census figures grossly underestimated the actual number of people, for those who are in this country illegally have a natural aversion to filling out official forms. Anyone who lived in the Los Angeles area during the decade of the 1970's will readily attest to the vastly more crowded conditions than the city's official 4.9% increase recorded by the census takers. Aside from all of the legal and illegal newcomers, thirsty mouths all though they may have, the officially recorded increases translate into added state and national representation. State and national legislators tend to represent the interests of those who supply their incomes, official and unofficial. Reapportionment, shortly, will add political influence to those who want more, ever more water.

More people choosing to live in the West and Southwest do not constitute the primary source of the nation's growing water problem. The American high plains, to the east of the Rocky Mountains and stretching 800 miles from South Dakota to Texas, sits above the Ogallala aquifer, an underground reservoir large enough to have once held as much fresh water as Lake Huron. In this region of minimal rainfall, a region once designated "The Great American Desert" on maps, irrigation and pumping water out of that aquifer supplies the 10-million-acre agricultural industry that is the pride of the nation. But, as we know, man does not live by pride alone; he needs bread. And those huge grain surpluses help redress the nation's foreign trade and balance of payments deficits.

Plains' agriculture mines the ground water at a rate that indicates it will be either gone or too expensive long before Saudi Arabian oil has been exhausted, or American dependence upon it severed. In 1900, the total irrigated acres in the United States numbered about 4 million. By 1981, that number exceeded 40 million nationwide, an increase in excess of 4,000%. More significantly, some one-third of the total dollar value of all American agriculture results from irrigated sources. Keep in mind, therefore, that the issue is not simply one of city people conserving; it is not even simply a matter of curbing urban development and growth—though strong arguments have been made for both. The issue is more fundamental and is central to the continuance of the nation's current political and economic system.

In parts of western Texas, the water table now drops an estimated 20 feet a year. In addition to deeper and deeper wells, and their requisite larger and larger pumps, that state has already dammed and "reservoired" every available river. In New Mexico at the end of 1980 ground water accounted for 50% of the state's consumption. The city of Albuquerque, in and around which nearly one third of the state's population lives, draws 95% of its water supply out of the ground. And the water table continually drops....

The state of Arizona, with which southern California has fought many a legislative and judicial battle over Colorado River water entitlements, has seen its population grow by over 50% in the decade of the 1970's. Water from the ground by the end of 1980 accounted for more than 60% of the state's water supply, with some places, such as the city of Tucson, totally dependent upon ground water. Between 1915 and 1980, as estimated 35 trillion gallons had been extracted. A recent governor of Arizona stated the situation bluntly: "Ground water is the single most important issue before this state. "

By the end of 1980, overdrafting had reached 2.5 million acre feet a year. The water table, the upper level of the aquifer, had dropped as much as 400 feet in some places. More ominous, the ground itself is subsiding, causing compacting and the permanent destruction of the aquifer's capacity to be recharged. Between Phoenix and Tucson, for a single example, a 120 square mile area has already dropped from 7 to 12 feet. No enactment of the state or national legislature, not even an emergency proclamation by an American President, can raise the ground back up . . . or stop further subsidence and compacting. Once again, as in the case of California, excessive water consumption results not simply from urban and residential development, but from the nearly 90% of the ground water used for irrigation.

The completion of the Central Arizona Project will directly and immediately affect southern California, particularly Los Angeles. Beginning in the mid-1980's, massive amounts of Colorado River water will be diverted into Arizona. At that time, the Metropolitan Water District of southern California will have its allotment from that river reduced by 50%. The prospect of that cutback spurred many southern Californians to promote the construction of the Peripheral Canal and the diversion of more northern California water to the southland. Only one of the ironies of all these legal battles, aqueduct construction and water diversions is that for the three Arizona counties served by the new Arizona aqueduct, the projected overdraft of the aquifer will still be nearly 2 billion acre feet a year, a rate which vastly increases the lowering of the water table.

Almost as if it had somehow or the other decided that an already critical situation was not critical enough, the United States government in cooperation with several of the nation's energy corporations insists that the Colorado River, in addition to all of the other demands upon it, can supply enough water for several and various " synthetic fuel" program developments. Coal gasification, coal slurry piping, and the extraction of oil from shale require huge amounts of water, the exact amount depends upon whether one talks to a proponent or an opponent of the program. The national government proposes to spend billions of the nation's taxpayers' dollars, with a single plant currently estimated to cost in the vicinity of $2 to $3 billion. Naturally enough, these programs and schemes promise "energy independence" to the American people. Unfortunately for the credibility of the program and the promise of independence, many of these same energy corporations and the same United States government promised in the 1950's that electricity from nuclear power by the 1980's would be "too cheap to meter." Public safety and health considerations aside, and obviously to many in government and industry those considerations have been placed to the side, I have heard of no one's electricity bill declining recently. Perhaps 1981 is still a bit early in the 1980's.

The fate and the future of the Colorado River Aqueduct, as well as of the Colorado River itself, remains entangled and unsnarled amidst all of the conflicting and contradictory claims to that once proud and magnificent river's annual flow. Obviously, in any given year, the amount of the river's flow will correspond to the amount of that year's precipitation in the Rocky Mountains' and will never exceed 100%. The whole of the river's flow, that 100%, must always be the total amount available to all of the present and potential users. Some forms of mathematics and percentages are rather simple. No one has yet devised a method to extract from a river, even the Colorado, more water than that river carries. The Navajo Nation, in 1980, for one last example, initiated legal action to establish their right to about 5 million acre feet a year of Colorado River water. Even if they do have a right to the water, and even if they win their litigation, more than 100% of the river's flow has already been promised to present and future users.

VIII

Aside from what those who currently control the decision-making process that affects the future of states high up on the Colorado River, certain very fundamental and extremely basic ecological and resource decisions and allocations have to be made—and are going to be made—in the immediate future. A gloomy prognostication based upon the historical record indicates that these decisions and allocations will serve the short-range interests of those powerful enough to control them. Yet, the entire nation—that is, all of the American people, including posterity— possesses a proprietary interest and right in their country's resources and its future. And perhaps their awareness of those rights and interests will grow and sharpen under the coming adversity. It has happened before. As Franklin said 200 years ago, "We learn the value of water when the well runs dry." What might we learn when, in addition to the wells, the rivers also disappear?

Southern California's desire for the construction of the Peripheral Canal which will greatly increase the carrying capacity of the California Aqueduct stems not only from the fact that the southland will soon have its share of Colorado River water reduced by 50%, but also from the realization by many people in the water business that the local ground water supplies are being depleted. The depletion of the water in the under ground reservoir increases the chances of pollution. With less and less water to dilute the various minerals and salts that arc naturally present in the ground, their concentration increases . . . the water becomes less and less usable for either people or for agriculture.

And of course most tragically, many manufacturers of noxious and toxic products have used convenient holes in the ground to inexpensively dispose of their wastes and by-products. Whatever gets buried in the ground eventually seeps into the ground water below—and the pumping of that water out of the ground places those pollutants into the city's water system.

Decreasing amounts of water in the ground increases the level of toxicity of those disposed wastes. Dozens of wells in the neighboring San Gabriel Valley had to be permanently closed during 1979 and 1980. And while the alarm has not spread to the San Fernando Valley, until the city's Department of Water and Power can provide an alternative source of water to take the place of the ground water, it really has no option but to continue to reassure the citizens that all is well . . that they know what they are doing.

Probably the city expected to make up any shortages with additional water from Owens Valley and Mono Lake Basin. Both areas, the first in Inyo County and the second in Mono County, have taken their predicament to the state legislature, the courts and the media. In November, 1980, the voters in Inyo County overwhelmingly voted to take back control over the ground water in Owens Valley. Los Angeles, in order to maximize the flow of water through the two Los Angeles-Owens Valley Aqueducts, had increased the pumping of that valley's ground water. Los Angeles owns most of the valley's floor, which would apparently include the right to the water below. Inyo County thinks otherwise, and it will be some time in the state courts before the issue is resolved. But by then, Los Angeles' public image, already not excessively high state-wide, will have suffered another tarnishing. And no doubt the responsibility will once again be laid at the door of the San Fernando Valley, probably just about where the Owens Valley Aqueduct enters the Valley.

IX

The California Aqueduct, or the State Water Project, as it is officially known, consists of a main canal 445 miles long, with over 100 miles of branch canals of varying sizes. At the end of 1980, 20 dams and reservoirs captured, stored and released the water from the Sierras when required. Seventeen pumping plants push the water all those miles and to a height of over 3,000 feet. And five hydroelectric power plants built into the system generate the power to propel the water southward. Just over the Tehachapi Mountains from the San Fernando Valley, the Edmonston Pumping Plant lifts the water the final 2,000 feet to an elevation of 3,165 feet above sea level.

From there the water flows by gravity into the San Fernando Valley, into the water system of Los Angeles, and actually into the water distribution system of all the members of the Metropolitan Water District. The multi-billion dollar project is supposed to work this way, but that assumes no political, economic or ecological opposition. And, really, when was the last time that anything complicated worked according to " the plan" ?

In July, 1980, California Governor Jerry Brown signed into law a multi-billion dollar expansion of the State Water Project. Generally and popularly known as the Peripheral Canal Measure, the first action is to be the construction of a 43 mile long and 400-foot wide earthen canal to carry Sacramento River water around the delta. That legislation also authorizes a complex construction program that will eventually double the capacity of the already existing 445-mile California Aqueduct.

The 1980 governor, one who had some years earlier warned Californians of the "limit on our resources" and asked the " serious question about how we grow and in what respect, " finally acquiesced to the fundamental forces that control and dictate the state's water policy. His father, Pat Brown, governor during the booming years of 1958 to 1966, at least never equivocated about what he believed and wanted: "I was a builder," he once recalled. "I loved to build freeways, bridges . . . I wanted to build that goddamn water project. "

The governor of California for the eight years between the two Browns, Ronald Reagan, later became President of the United States. Not one of those three, nor any of those who came before, stood firm against those who wish to make personal and gainful use of the state’s fundamental resources . . . particularly water.

X

Unfortunately for most Californians, the continuing controversy over who is to get the water, who is to be the next speaker of the California Assembly - a northern or southern Californian— continues to neglect the larger issue that southern California is ecologically part of the American Southwest; it is not ecologically part of the 1850 political decision that created a State of California. It may be true that "in love, opposites attract"; that cliché has little or nothing to do with political and economic associations. Perhaps California ought to be two states. But it is not, and all of the various attempts to separate California into two states will no doubt flounder on the granite reefs of powerfully entrenched economic and political interests. One does not have to be a disciple of "Darwinian Evolution" to realize that any and all successful organisms, particularly those called economic and political interests, have learned not only the value of survival but also the mechanics of successful adaptation.

The State Water Project, the California Aqueduct, involving the delivery of more and more water from northern California to the southland, is not going to work. First, the water and its delivery will cost ever more and more. From that inevitability there is no escape, and the excessive cost will eventually price it out of all reasonable markets. For fresh water, there is no substitute, remember. Perhaps more importantly, northern California water will probably not be available to southern California when it is needed—at any price.

Increasing resistance from northern Californians and the various users along the way south together are likely to be enough to cut southern California off. As mentioned above, during the 1975-76 "drought, " Los Angeles was in fact shut off from the California Aqueduct water. Whether this was a voluntary action on the part of Los Angeles, or a mandated one on the part of the state matters little: the fact is that when the water was needed the most, it was not available.

A second major obstacle to the increased diversion of fresh water from northern California and from the delta involves the little understood problem of salt water intrusion. The Sacramento Delta, around which a peripheral canal is to be built, supports one of the state's most important agricultural regions. Fresh water from the delta is now being pumped south. And large urban and industrial centers, such as the Oakland and East Bay area, already use the delta for their major source of fresh water.

Any diversion of fresh water away from the delta added to the increasing amount being taken out, will necessarily decrease the amount of fresh water available to support all of the various elements that depend upon that source. And no less important, salt water coming into San Francisco Bay from the ocean, and then moving from the Bay up the straits toward the delta, is kept back by the pressure of the delta's fresh water that flows westward. Any diminishment in that pressure will obviously allow the salt water of the ocean to work its way inland. The delta itself could eventually become too salty to support the urban, industrial and agricultural complexes that depend upon that fresh water.

Finally, and independent of what all those hundreds of thousands of people are supposed to do— to where they are all to go, as the salinity level of the delta increases, the water being pumped out of the delta at Tracy for shipment south will itself become increasingly unsuited for the very purpose of the entire project. What farmer of the San Joaquin Valley or what resident of the San Fernando Valley wants water of an increasingly high salinity content? What would they use it for?

Various politicians and others who earn their living by making impossible promises to their respective constituencies have yet to devise a way to hold back the salt waters of the ocean. The success of California's State Water Project, the Peripheral Canal being the most recent—though not last—addition, depends upon the ecological health of the delta. It requires holding back the salt water from the ocean, which means it demands a certain steady flow and pressure of fresh water westward to hold back that salt water. Of course, a few free flowing rivers along the north coast of California continue to run toward the ocean. Perhaps these could be dammed, "reservoired" and their water pumped eastward over the coastal mountains into the upper Sacramento Valley. Perhaps.

XI

North of San Francisco, the inhabitants of such remote counties as Humboldt, Trinity, Lake and Mendocino are organizing and articulating their very real concern that the megalopolis, the Empire that is southern California, will soon be reaching into their lives, dipping into their water supplies. The few still free-flowing rivers attract dam builders. If those free-flowing rivers, rivers flowing into the Pacific Ocean through the redwoods and the last of California's salmon and steelhead habitats, can be dammed and the water diverted inland, eventually into the proposed Peripheral Canal, well, that will be just so much more water for the ever-thirsty southland, though the costs in money, energy and environmental degradation continually rise. More of the same.

Move water from where it is to where the developers wish the people to live? Turn semi-arid and desert areas into agricultural, suburban, commercial and industrial islands on the land? Turn water-rich and independent regions of the state into colonies, often into deserts?

The fate of Inyo and Mono Counties, colonies of the Imperial southland; the increasingly apparent ecological fragility of the entire great Central California Valley; the equally apparent unconcern, disregard—hostility, even— for matters of environmental quality obscenely visible even on a clear day, when weighed against present economic gain, pass not unnoticed when the northerners look south, particularly among those northerners who themselves have fled, or have escaped, the southland.

Generally speaking, the relationship between the water supply in Owens Valley and in Los Angeles is reflected in a similar relationship between northern and southern California. That is, when there are abundant rains and snows in the north, the north cares little how much of their water is shipped to the south. But, again generally speaking, when a dry period or drought hits, it strikes both regions; thus, a shortage in the north with the scarcity and panic shortage causes parallels a shortage in the south with the increased demand that it causes. Again, a fundamental contradiction.

Northern California considers water to be one of their resources, to be used primarily for their agricultural, residential, urban, business and industrial purposes. Perhaps this is a most parochial attitude on their part. After all, we are all Americans, all Californians; what right have they to proclaim riparian rights when southern California's need is so obvious, so great? Southern California does have immense political power in Sacramento relative to northern California; generally speaking, it also has much greater financial clout. Together, these have already provided southern California with the Owens Valley Aqueduct, and the California Aqueduct. But resistance grows each day, as growth and development proceed in the north.

A not insignificant matter is the problem of irrigating the great Central Valley of California: the Sacramento, in the north; the San Joaquin in the south. A continuous expansion of the area under cultivation—and we do need increasing amounts of food to feed the increasing numbers of stomachs at prices that those stomachs can afford—requires an ever increasing amount of water available for irrigation.

The Sierra snows which provide the runoff into Owens Valley on the east side of the mountains also provide runoff for the west side of those mountains. Those snows and the rivers which they form provided the original water supplies for a moderate amount of agricultural activity in the Central Valley, more moderate in the southern portion than in the northern, of course, for there is simply less snow in the southern Sierras than in the northern . . . and thus less water runoff. As agricultural development increased, and continues to increase, together with the necessary support systems—towns, processing plants, people—the demand for water necessarily increased, and increases. Another dreary inevitability; another fundamental contradiction—who is to get that water? The farms with their dependent and necessary industries and towns through which that water flows, or the regions, cities, towns, the San Fernando Valley to the south?

Complicating all this is another rather elemental fact: most of the farmland through which the California Aqueduct flows southward is owned or controlled by a few huge agribusinesses. Count, some time, the number of acres owned or controlled by the Southern Pacific Land Company, a subsidiary of the Southern Pacific Railroad of "Octopus" notoriety (see Chapter 6 and 12); count up the number owned by the Kern County Land Co. Indeed, remember that over 50% of all of California's arable land is owned by a mere 45 corporations. Now that represents some considerable political and financial power, considerable enough that state and national political figures purporting to represent Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley will necessarily think more than twice before contesting those 45 for water.

XII

Who owns the water or, more importantly, who controls the water, controls the land—the land that was relatively unproductive until either the federal or the state government, with the monies of the taxpayers, brought the water to that semi-arid land. The consumer of food, therefore, pays twice. State and federal taxes went and go to harness the rivers, build the dams and reservoirs and construct the miles of aqueducts and canals which deliver the water necessary for agriculture to flourish. The consumer pays again at the grocery store, where agribusiness can exact high prices for the food because their monopolistic power in the marketplace enables them to administrate prices. A particularly bizarre aspect of all these machinations is that they are mostly illegal, and everyone involved knows it. The law is simply not being enforced.

Under various legislation, some going back as far as the Newlands Act of 1902, farmers may not make use of federally subsidized irrigation water for farms in excess of 160 acres. Farmers are under no compulsion to sell their land; they may have as large a farm as they wish and are able to maintain. But they may not use taxpayer financed water for that land in excess of 160 acres. Throughout much of the West, irrigated agriculture depends upon ground water. Mining the ground water to irrigate huge corporate farms may lead to ecological disaster, but it is legal. It is primarily in California, where fresh and usable ground water has long been either in inadequate supply or too expensive, that the law goes knowingly and willingly unenforced.

A strange alliance operates to prevent the enforcement of the 1902 Newlands Act: the alliance between the urban centers of southern California and the corporate farmers of the San Joaquin Valley. The promoters and developers of the spreading urban real estate need the northern water to sell their residential and industrial merchandise. Private lakes surrounded by exclusive communities of individual homes or condominiums and the plethora of swimming pools visible on clear days from the sky all ostentatiously consume. Steel mills, oil refineries and power plants require even more fresh water, though they may be less conspicuous in their consumption. The promoters clearly desire no obstructions to their developments, certainly nothing to remind anyone that the area being developed in essentially a desert.

Join the power of these interests with those of the huge farm corporations of the San Joaquin Valley, and you have a combination that no sensible politician will oppose. So, federal and state water systems continue to operate and expand, providing fresh water from the taxpayers' trough. West of Fresno, for example, is a region known as the Wetlands. In this area, now being irrigated with subsidized water, expensive aqueducts and increasing demands upon northern California resources, the Southern Pacific Railroad owns 110,000 acres. Standard Oil of California owns 11,000. And other large American corporations own amounts that vary between these two.

In that same Wetlands region, Jubil Farms, owned by Japanese interests, financed a most complicated purchase, buyback, lease and leaseback arrangement to some 12 square miles in order to get around the 160-acre limitation. In the Sacramento Delta, Martel Company owns 2,500 acres. With its headquarters in Curacao, in the Dutch Antilles, according to a 1980 study done by Maria Baker, this company "is a wholly owned subsidiary of the Halix Investor Corporation, a Panamanian firm with a Swiss address. " Complicated . . . apparently too complicated for any of the state or federal attorney generals. But the absurdity continues. In February, 1980, the federal government granted $24 million in relief funds for flooded Sacramento Delta farmers. Not only did Martel Company receive some of the benefits, but according to Baker, so did Juve Investment Company, "another Curacao-based company that owns 3,203 acres of land in the delta."

Selling America, the farm land of America, to absentee foreign landlords is probably not a good idea. Ironically, allowing the 160-acre limitation to go unenforced all these years has already enabled absentee American landlords to acquire landed domains more like medieval baronies than the small, independent and proud family farms that Thomas Jefferson had hoped for the American future. |

The South once lost a war, but that one was over a century ago and involved slavery, states' rights and secession. In California, the South may well win this time. It has the economic and political power on its side. But what if the ever urbanizing southland did win? If additional supplies of water are to be made available to southern California, who is going to pay for them? And what manner will the payment take? Just as certainly as there is no such thing as a "free lunch," there is no such thing as free water—not for people who choose to live, build, irrigate, industrialize and urbanize arid and semi-arid regions.

Rising land costs, rising water costs, rising energy costs continually affect each other in an interrelated manner only recently detected. Each affects the other, causing a disproportional rise in all, another spiral from which apparently there is no escape, politicians' continual promises to the contrary notwithstanding. Another fundamental contradiction . . . apparently. Someone has to pay for additional dams and reservoirs in the north. Someone has to pay for the tons and tons of concrete, for the miles and miles of drainage ditches, aqueducts and canals. Someone has to pay for the generation of the electrical power required to pump all that water all that way.

Suggestions, anyone? Try the taxpayers of Chicago, of Atlanta, of the United States generally.

What do you think? How about the northern Californians, from whom the water is to be taken? Are they likely to be reasonable about this, which from their point of view is simply subsidizing the thief for the act of stealing from them?

Ah, how about the users? And which users: agricultural, industrial, residential? Any way the loaves and fishes are distributed, the consumer is going to have to consume less and pay considerably more. Charge the farmers more, or reduce the amount allotted to them, and food prices go up . . . that's simple. Also simple, charge the industrial and business users more, and guess what they will do with the increased cost of doing business, of manufacturing? Pass it along, naturally. And, naturally to whom?

XIII

The naturalist Elna Bakker explained in her introduction to California's ecological communities, An Island Called California:

Life has not found deserts to be impossible places; however, there are secrets to survival here. A shrub can spend water when it is available, but it does so at its peril when moisture is in short supply.

A "water balance—a moisture loss equivalent to moisture intake—is essential for all plants if they are to continue growth," is Bakker's blunt warning to all of us, even those of us who consider ourselves farther up some evolutionary ladder than mere plants.

The need for fresh water remains a fundamental issue. It is most unlikely that humans, along with other earth-dwelling forms of life, will be able to adapt to either its increasing toxicity, its increasing salinity or its increasing unavailability. As energy shortages and rapidly rising energy costs were a traumatic feature of the 1970's, fresh water shortages and even more traumatic increases in related water costs will shatter what remains of the optimism and complacency of the American westerner, most particularly the south westerner, and specifically the southern Californian.

Realistically, current users cannot be charged for the cost of providing the necessary water. The resulting high costs will demonstrate the extremely limited capacity a semi-arid region has for additional growth, and that would hurt speculators, the backbone of the southern California business community. You cannot sell real estate to corporations or to individuals if you have to tell them the blunt facts of life, and the price of those facts.

Probably the traditional American way will be utilized: sell bonds and let the future worry about it. "Cut and run," some call it. It works this way: sell bonds today, increasing the public debt, and raise taxes tomorrow to pay the interest and principal on those bonds. That way, apparently, everyone is satisfied, except those taxpayers of tomorrow who will have to pay higher and higher taxes of all sorts. And every taxpayer will raise prices to cover those increasing taxes—including those working for wages who will have to demand higher and higher wages to cover the higher and higher rents, mortgage payments, food prices, and all the rest. Maybe all of this sort of thing can go on forever. Probably, it can not. xxx

--- Lawrence C. Jorgensen, 1982