14/Generations

INTRODUCTION

The phenomenon of the San Fernando Valley in the first 80 years of the 1900's stands as a unique time in history largely because of the pace of growth and change during that period. The area has drawn millions of people in search of a dream, and, regardless of the time of their coming, many of their experiences, attitudes, and impressions are remarkably similar. When seen through the eyes of actual individuals whose ages range from 80 to 25, the objective facts and figures of historical reporting become instead the subjective experiences of real people with whom we can identify.

This personal narration begins with Lynn Langford, who was born in the San Fernando Valley before World War II and grew up during the Forties and Fifties. Whitley Van Nuys Huffaker is recognized as the first baby born in Van Nuys, and has lived his entire life in and around the townsite. Sam Greenberg and Harry Bevis, the Valley's oldest World War I veteran, both came to the Valley before 1920 and watched the steady growth.

Kurt Sechooler arrived here when he was 8 years old and presents the Valley and his personal experience from a sociological point of view. Doug Sizer is a relative newcomer, moving here in 1974. His sharp eye captures the unique aspects of Valleylife (particularly the architecture and plant life) which every newcomer has surely seen, and which inevitably fades with time. — Susan Siegele, 1981

I

I am a product of that generation which came to the Valley between the World Wars looking for the "good life." They came to grow fruits and vegetables, to raise livestock and chickens. The soil beneath their feet was rich, and water was obtainable. Their children played in the orchards and their neighbors were friendly. Their jobs as ranchers, farmers, shopkeepers, and tradesmen were inter-related to each other's basic needs—food and shelter.

Of course, the promise of the "good life" was all fantasy. The Valley grew, and the growth was directed and manipulated by the real estate speculators. The second wave of growth, which came in the Fifties, included many couples who were moving to the San Fernando Valley with the same fantasy that brought my parents here before World War II. The spirit was still a "home of one's own," with some land for a backyard; a place of solace and a safe place for one's children.

There was a brook near the end of Mulholland Drive, and in the late Thirties and early Forties we crossed innumerable small streams as we hiked the canyons and built hideaways among the oak trees. In the open areas near my home were a few scattered men who camped or built shacks. Some had a few sheep, while others kept small vegetable gardens or a few hens.

My mother told me the men were called hermits and were very poor, butt later I heard them called "bums" when my parents thought I wasn't listening. I was too young then to know almost the residual Depression poor.

When I took my solitary walks, I often used to talk to one particular man who always seemed to have time to talk and who patiently answered all my questions. He taught me how to build a pond by damming up a stream, and he explained to me the importance of being careful to allow a slow trickle of water to escape so pressure would not destroy my wading hole.

Ten years later a bulldozer came and pushed dirt over my "little streams" to create Longview Valley Road, Coy Drive, and Casa de la Cumbre. I often heard people speak of seepage in their backyards, and one rainy day a few years later, the pressure sent torrents of mud and homes sliding down the hills.

My father was born in Arizona when it was still a territory. He left to search out his destiny early in his teenage years, going first to Virginia City in Nevada. He worked the silver mines but soon grew restless and left for San Francisco - the "big city." He took all his earnings and purchased a small boat which he and a partner used to set up a hauling service between San Francisco and Richmond. He felt smug and proud of his new career and of "getting ahead" at such an early age. But his success was short lived: during a storm, a wave capsized the boat, drowning his partner. Broke and alone, he returned to the desert, never again to go to sea.

He rode the range with the cattle in Mojave and played the rodeo circuit after World War I, but it was a lonely life, and he wanted a family. He moved to Los Angeles where he became a tile contractor and worked for himself in the Valley.

In the early Thirties, he brought his bride to the Valley side of Mulholland, in Sherman Oaks. Here, he said, was the perfect climate, and he especially liked the cool breeze that blows down Beverly Glen Canyon. My mother liked it because it was not far from the city, yet she still had the country for growing flowers, trees, and vegetables. As children, we were safe from congested city streets, free to run the fields.

They purchased an acre lot on Millbrook Drive for $700. My father cleared the land with a team of mules and often bartered his trade as a tile contractor while he built the family home. It was two stories with three bedrooms, two bathrooms, and a detached garage which also had a bedroom and a bath. It cost $5000.

My parents terraced the sloping hillside and made retaining walls from rocks found in the Santa Monica Mountains and brought home from the desert. While working the land, my father found two large heavy stones which had been worn away as the Indians ground acorns they had gathered from the oak trees. As children, we were always aware of the Indian spirits remaining in the Valley. We took it for granted.

In the late Forties, my parents added another room and bath to the house, plus a swimming pool for us. In 1963, my husband and I added a family room, two bedrooms, and a bath with a Japanese tub. We also repainted and redecorated the original part of the house, and in 1968, we sold it for $82,000. It was resold in 1976 for $110,000 to a builder who modernized the kitchen, updated the decor, and converted the badminton court into a tennis court. He sold the property for $250,000. So it goes….

The years from 1935 to 1955, which I spent growing up in the Valley, were years of gradual change. There was still a "small town" feeling, and, regardless of whether a person was a movie star with an expensive "ranchero" or a poor chicken rancher, we all visited the feedstore on Moorpark and Woodman Avenues for the same reason. Sometimes I rode my horse to visit my friends, or took my pony cart down Van Nuys Boulevard where even the drivers were tolerant of children on horseback crossing an intersection.

I felt carefree, but I soon lost my innocence. In 1941, when I was a child of six, I learned about vegetables and flowers from our Japanese gardener who had a very real love for growing things. He gave me a hand painted picture postcard of Mt. Fuji, and told me that it was a "peaceful mountain. " One day he told me that our country was having a "fight" with the country he had come from. He wanted me always to remember that "the gardeners, the fishermen, the mothers and fathers, and the children aren't mad at each other, and everyone loves flowers."

Then one day he was gone, and I missed him. My mother simply told me that he "went away." I was very angry that he hadn't told me where he was going or hadn't said goodbye. Later, when I understood that he had been taken to a concentration camp along with many other Japanese-Americans, I couldn't understand why a war which was so far away could affect us in the Valley.

Our teenage years in the late Forties and early Fifties were a time of "ideal" love and living, a time of companionship and sharing. We all rode the Red Car together, and a "big night" was going to a movie at the Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Hollywood. Afterwards we would go have a hot fudge sundae at Brown's Parlor.

But all too soon, the Red Car was gone; we were told, "It is not needed." So we retreated, two by two, into the isolation of the Automobile, and learned to "cruise the boulevard." We strutted through Bob's Drive-In in Toluca Lake and on Van Nuys Boulevard like peacocks, our radios blaring our music.

I was away from the Valley for much of ten years. When I moved back in the Sixties, I found it crowded in, my childhood home surrounded by neighbors. Schools, homes, small industry, shopping centers, theaters, and recreation centers, restaurants, chainstores, medical centers and freeways intermingled with the neighborhoods, filling the needs of the people in an overcrowding materialistic society. For me, this new growth made the Valley lose its pastoral feeling.

I was amazed at the changes along Ventura Boulevard. The small grocery store had disappeared. The drug store with its friendly fountain at Van Nuys and Ventura Boulevards was gone. Pete no longer sold his corn on the corner; he was replaced by a shopping center. The cobbler was out of business, and the corner of Moorpark and Hazeltine Boulevards, where I took my riding lessons, had become an apartment complex. Across the street, a modern "Ralphs" had replaced Mr. Ralph's market. A bank stood where I took my swimming lessons.

But the worse change of all was the loss of personal contact. The increasing inflation separated the people into tighter class distinctions, and the increasing alienation left me unconnected, watchful and alone. I felt frightened. I needed to grow vegetables, and I wanted to know someone when I marketed. I was lucky enough to have the chance to change. I left. -- Lynn Langford, 1981

II

At the end of World War II, the San Fernando Valley was little more than some land north of Los Angeles. The development of that real estate is the story of the economic, social, and cultural development of post-war America. In the space of one generation the Valley has grown from a sparsely populated patch of land to a city with a population of one million. Amazingly, this growth occurred without a corresponding development of any form of public transportation.The Valley is "Motor City America," and to have grown up here is to have experienced the most exaggerated individual mobility in history. After the Great War and the Great Depression, the people who had experienced a youth of forced conservation and economic deprivation eagerly relocated to an area where more than sufficient personal space would allow for real concentration on personal consumption. The automobile and cheap gasoline made distances which were prohibitive a generation ago easily accessible. People readily drove from the Valley through Laurel Canyon and Cahuenga Pass, or over Sepulveda Boulevard to work in Hollywood and Los Angeles.

The Valley was principally settled by a demographic group known sometimes as "the Coolidge Generation," or "the Class of '46." This group of people who were born around the same time (known as a cohort group) was dominant throughout the Fifties and Sixties. The national demographic center of gravity in 1959 was 39 years of age. These were the pioneers who settled Reseda, Northridge, Van Nuys, and the other post office zones that comprise the Valley.

Having experienced adolescence during the Thirties, these people were very much concerned with employment, economic security, and consumption. This attitude matrix was generally manifested as a "concern for money," although property values, capital gains, and pure status considerations were also involved. When the motivation provided by these attitudes was coupled with cheap land and low energy costs, the result was prodigious economic growth.

Housing costs in the Valley were amazingly low, allowing even working class couples to buy their own homes. With the cost of shelter fixed over time, it became possible to devote more income to other forms of consumption; by the early Sixties, three car families were not uncommon, elaborate garb known as "Ivy League" became very fashionable, and to ease the heat, home swimming pools were installed.

I was a high school senior when President Kennedy was assassinated. The Beatles were just arriving, and a few of us were already listening to Bob Dylan. We drove through Laurel Canyon, "over the Hill," to places such as the Unicorn, Chez Paulettes, and the almost legendary Fifth Estate on the Sunset Strip. Gas was a quarter a gallon then—a buck's worth was all you needed.

Whereas the Fifties were a period characterized by the middle-age concerns of the demographic center of the time, the coming of age of the "post-war baby boom" babies initiated a dramatic change. By 1964, the demographic center of gravity had shifted from age 39 to age 17, and the volatile Sixties were born.

It has often been said that social and cultural change in America begins on the coasts and works its way inward. The "hip" movement of the Sixties started in California, and the youth of the Valley were charter members. Raised in a period of affluence with the finest educational system available to them, this new generation found itself with abundant time and energy for questioning the "status quo."

The result was the launching of a major assault on the values of the older cohort group. The battleground was essentially drugs, sex, politics, music, dress and, of course, hair. But the major point of contention was America's involvement in the Vietnam War, and the draft. Although not all members of that generation were involved in rebelling against the "Establishment," they had been born in such great numbers that even a small percentage of the whole had an undeniable effect.

In the final analysis, the truly significant confrontations of this era took place not at Century City, San Francisco State, or People's Park, but in the thousands and thousands of living rooms across the country where the clash of values and attitudes tore families apart. Ultimately, the Sixties were, in the words of Dickens as he spoke of the French Revolution, "The best of times and the worst of times." A time of high ideals and drug overdoses.

The Valley will never again see a period of economic growth like the one that took place in the Fifties and Sixties. The unique demographic pattern and resource related structure will not occur again. Yet this does not mean that development cannot take place. The loss of individual mobility that has already begun, as a result of upward spiraling petroleum costs must be compensated for by public transportation and greater community involvement. We have reached the end of an era, and we must modify our image of what "life is like" to reflect the economic, political, and social realities of our lives.

Perhaps the most important thing to remember is that the end of one era is the beginning of another. Psychologists tell us that human beings are resistant to change because it creates stress, but we also know that without stress there is little motivation. Growth does not take place at a constantly increasing pace. Just as there are periods of growth, there are also periods of consolidation and conservation.

We are now in this later period, and we have a choice as to the direction and attitude it takes. It can be, as in the Thirties, a period of forced conservation, or it can be a time of management and control. When we change our collective image of the Valley and see that in the future it can be a place where there is adequate public transportation, less congestion and a greater sense of community, we have taken the first step towards control. In the final analysis, it is those with the clearest vision of what they want who will prevail.

The burning issues of the Sixties have melted away; the apathy of the Seventies has given way to the anxieties of the Eighties. The era of twenty-five cents a gallon gasoline is over, housing is no longer inexpensive, and interest rates have become historically high. The " postwar baby boom" babies have passed from adolescent rebellion to unemployment. And even at over a dollar a gallon for gasoline, the freeways are jammed, the major streets congested, and the air not only unbreathable but dangerous. One thing remains the same, though—the bus system is still worthless. -- Kurt Sechooler, 1981

III

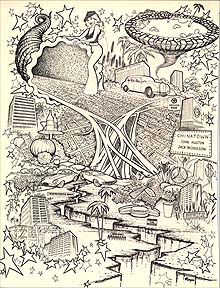

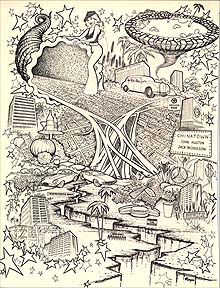

In many ways, the San Fernando Valley seems to be little more than an extension of the myriad studios, both cinematic and musical, that it contains. An abundance of lush subtropical flora blends, and sometimes starkly contrasts with, a vast unwieldy synthesis of architectural styles. Just as the inhabitants have migrated here from all over the United States and the world, so too are the buildings derivative of every epoch and country. The complacency of the combination makes you shy away from the epithet "original" towards one like "commonplace." The San Fernando Valley is more than a melting pot, it is the epitome of southern California.

Like the fantasy land portrayed on prime time every night, the Valley embodies and extends the general drift of the American Dream in all its ostentation and ambiguity. Anything fits as long as it has "style," and the entertainment studios produce whatever will sell, no matter how questionable the taste or superficial the content. In this era of "me-ism" and "kitsch," or stylish pretension, with its striving to be different and unique, any style of living is acceptable, no matter how gaudy or scandalous, as long as it is interesting. The lifestyle of movieland is rigorous in all its seemliness and unseemliness.

A drive out through the Valley along Ventura Boulevard numbs the senses with its miles and miles of businesses. Yet it also elicits the feeling that you are in the thick of it — whatever civilization has to offer in the way of goods and services is yours for the asking — and for a price.

Like the Boston Post Road in Connecticut or the Hempstead Turnpike in Long Island, Ventura Boulevard is a ceaseless chain of commercialism: restaurant after store, bar after restaurant, motel after bar, store after motel. A boutique closes up and reopens as a yogurt dispensary; a nightclub called the Good News is metamorphosed, by new management, into After Hours. Yet for all the impermanence, the essence of the Boulevard remains constant.

The neon sign in front of a Sherman Oaks motel says it all: a red suited bathing beauty does a flip off a white diving board into a blue pool which is shaded by a green palm. In an instant, she is back on the board again, diving again. Perpetually in motion, yet frozen in time and space, the neon girl tugs at your heartstrings with her message that even change can be eternalized and fixed. The good life goes on forever; the endless vacation can be yours.

Long known as "L.A.'s bedroom," the San Fernando Valley is a hybrid community that has been skin grafted with a little of everything from everywhere. The only dominant theme in the construction here is no dominant theme, and, for that reason, some view the area as undistinctive. In Gebhard and Winter's Guide to Architecture In Los Angeles and Southern California, the authors make no bones about their feelings:" All you need to become a radical proponent of the ecology movement is to compare pictures of the Valley at the turn of the century to the reality of today. Nowhere on earth has the land been so wretchedly violated. We do not mean simply that it has been built upon. We mean that this architecture is almost uniformly, sometimes it would seem, intentionally, stupid." Despite this stark appraisal, they later admit, "We like it." For if there is one style of construction here, it is an International style. If you do not care for a great deal of the architecture, there will, however, be certain aspects that you love. The architects have endeavored to cater to everyone's taste. Chandler Boulevard is a perfect example. In the few miles between Coldwater Canyon and Van Nuys Boulevards, you can drive past all kinds of habitations. Hansel and Gretel cottage homes, with peaked roofs the color of gingerbread, sit next to Neo-Southern plantations of white wood replete with pillars and porticos. Stolid Spanish style stucco ranch houses, with portholes for windows, face Zigzag modern homes of natural wood shingles. Squat single storied fieldstone houses are juxtaposed with gabled and balconied Tudor manors.

It all blends together under the silvery blue green of the deodar cedars which run in rows down the boulevard, and no one style quite upstages another. Even the older tract homes in North Hollywood, Burbank or Van Nuys have their distinctive features. A rounded Moorish tower on a small pastel green stucco house becomes an angled dormer window on a yellow house; roofs of rounded red thigh tiles become roofs of flat rectangular tiles.

It is only in the newer condominiums, townhouses and tracts, particularly those sprouting up all over the fields of the west Valley, that the drabness and sameness of modern construction can be viewed. The cost of land and building materials has made distinguished housing available only to a wealthy few, and many new neighborhoods are plain and vacuform, as if poured from a mold. Still, with the cost of the average Valley home currently over $100,000, choices and sacrifices must be made. The new generation of home owners may not care for distinctive appearances as long as the amenities—pool, tennis court, sauna or hot tub—are provided.

Much of the Valley's attractiveness comes from its lush plant life, since just about anything seems to grow here. Laurel, the state flower of my home state of Connecticut, grows so well that it is used to border the freeways. Along with many other trees, shrubs, and flowers, the species of laurel that grows here is called California laurel. The big leaved, piebald barked, sycamore trees that grow in North Hollywood Park, and throughout the area, are called California sycamores. Appropriation and re-naming are rule of thumb here. Perhaps to come to California is to become Californian.

While easterners tend towards the English school of gardening, in which trees and shrubs are allowed to grow freely and are trimmed only when necessary, here the French style of gardening, in which trees and shrubs are cut and shaped to specific, unnatural forms, dominates. Teams of professional Oriental and Mexican gardeners are a regular expense, even in lower middle class neighborhoods.

Yards are laid out precisely, lawns are sculptured and trees become ornamentals while topiary hedges take the place of fences. Evergreen cypresses, depending upon the owner's predilection, are cut man size like lawn statues, or as high and looming as totem poles.

The feeling that the flora here is fundamentally ornamental in purpose, and similar in function to a movie prop, is increased by a visit to one of many tree farms in the Valley which offer 30-foot palms and firs contained in wooden or clay pots. Whereas in the East most of the trees in a yard were there before the house went up, here you order whatever type and size of tree fits your fancy.

Besides greenery, flowering trees and shrubs have been infused with those indigenous to the area. The white blossoms of the flowering magnolia are everywhere but, ironically, in greater ranks elsewhere than along the boulevard named for them. Chinese red bottlebrush, its bristles capped and dusted with gold, blooms early in the season. Mostly gone by the Fourth of July, it is replaced on cue by the violet and pink hues of the crepe myrtle, which lasts until September's perennial heatwave. Deep purple bougainvillea not only runs the length of the Coca Cola building in North Hollywood, but cascades royally over roofs and porches throughout the Valley. Flame orange pyracantha berries cluster as thickly as grapes in wine country while yellow and pink hibiscus opens its large petals like welcoming hands.

The coexistence of seemliness and unseemliness in the Valley is startlingly apparent on Ventura Boulevard. With eyes kept ground level, the boulevard proves to be an ordinary city street which could belong to any metropolis. But allow your gaze to ascend skyward, settling on the California palms, and the southern California ambience sets itself apart. The palms dispel a newcomer's apprehension that the area will prove to be just another homage to concrete. With their fibrous skirts of dead fronds that dance untouched in the blazing red sunset, the palms seem to promise that here nature will not be persistently excluded.

Yet as the newcomer journeys down the apartment-laden streets of the Valley, the promise is broken. One not only understands why foliage must be brought into the area, but also why Gebhard & Winter's term "violated" is apt. The remnants of citrus and live oak groves have been pushed aside by masses of "Tropicana," "Lido," and "Casa" dwelling units. Greenery is upstaged by stucco and, without the form fitting flora, there would not be much nature around.

Sardonically, the buildings lie in straight parallel rows just the way the orchards and wheat fields used to, retaining the linear feeling of the fields and groves they have supplanted. Because of the earthquake danger to tall buildings, structures must be short and wide. Thus, more land and greenery must be plowed under. Even the big homes are close together, often with small yards that barely encircle the structure.

Natural surroundings have also been displaced by an intricate system of alley ways. Just as the fronts of the studio backlots are for show and the backs for function, so too are the buildings of the Valley backed by twisting alleys. With parking lots and dumpsters behind business sections, secondary driveways, stocked garages, and trash cans found once a week behind residences, the Valley's urban sprawl reveals its similarity to Manhattan in its alley ways.

The lush lifestyle of the Valley is vanishing steadily at the hands of man. Too many people want to share the good life here, and the demand for placement is transforming the Valley from a leisurely, lulling community into an overdeveloped, unnatural setting. Luxury is on the wane, and the Valley is becoming the City.

The worst manmade re-structuring of the beautiful environment that once ruled here is the tarnishing of the air that we call "smog." In July of 1978, and again, to a worse extent, in September of 1979, a terrible brown sludge descended upon the Valley. Parks, sidewalks, and tennis courts emptied; hospitals, doctors' offices, and beds filled. The smog worked its way across the floor of the Valley, hanging about like an invading army, while government officials warned people to stay indoors. How bitter the irony that people have turned their neighborhood into a danger zone!

Yet there is also a sweet irony that goes with the southern California milieu of the Valley and its role as life support system for the entertainment industry. On clear days, when all around seems fresh and vivid, it is easy to forget the effrontery and discomfort of the smog. When Santa Ana winds rake the area, or after a wet spell brings snow to many of the mountains that rim the floor, the Valley not only looks lovely but gives off an invigorating, nearly paradisical feeling. The atmosphere is ratified, as it is in the Sierra or in a picture by Maxfield Parrish. Beautiful days such as these lull you into happily, or at least painlessly, accepting life, along with its smoggy side, just as powerfully as hours of television dull your sensibilities.

The real question is how fast the special quality which has drawn people here from all over the world, like disciples to a temple, will vanish. It may happen in the near future, for nature has always been a volatile force here. During recent years, the area has withstood weather conditions on a larger than life scale befitting a community that is home for the motion picture industry. The climate, too, overdoes its effects.

Heightened reality and dramatic events are not just the bread and butter of silverscreen dream merchants. Here, nature is the director, and the San Andreas Fault is the superstar who stands in the wings waiting to steal the show and close the curtain.

Newspapers called the summer of 1975 and the winter of 1976 "the worst draught in 72 years." The foliage of the Valley withered and browned while water was rationed and residents were often shocked by static electricity. Day after day the sun glared down ferociously and set in a fury of blinding red foreshadowing the inferno that was the Big Tujunga fire in January of 1976. Ashes fell like snow, the air tasted charred, and the sky was as nightmarish as it must have been over Pompeii after the volcano.

Still, too much water can be as destructive as too little. When the seasonal rains strike, entire streets, such as Saticoy east of Sepulveda, become impassable rivers. Throughout the Valley, cars stall and die only to be inundated by walls of water sent lurching by passing vehicles. Roofs leak and collapse; houses slide down hillsides.

There was and still is a traditional California look to the Valley—a special dramatic vitality in the setting that has drawn people here for over a hundred years; an aura of possibility that pulled the billion dollar entertainment industry out of New York City. That you can love that look and hate watching it disappear is the main ambivalence about living here. You can feast your eyes and feed your mind on the exotic flora. You can be fascinated and amused by the heterogeneity, showmanship, and style of the architecture. But you cannot deny to yourself that it is increasingly difficult to see the beautiful and the special.

The foreseeable future of the Valley has been most succinctly expressed by a visionary Cassandra who painted a mural on a concrete pylon at Hayvenhurst Avenue under the Ventura Freeway. Overhead eight lanes of traffic are snarled in the daily madness of rush hour. -- Doug Sizer, 1981

IV

We all appear so pressed for time the days crowd themselves into the past like eager people pouring into some first-run movie house like chicken scratches on a prison wall, each one bringing some lonely soul closer to release each day gone brings us nearer to all the imagined future conquerings.

Up in neon lights, posted on the marquis, the announcement glares out its promise. In red and green "FAMEANDFORTUNE" begs us to come on in "get your share" you know it's only fair that you should get your share. In this day of hectic ramblings it takes fight to get your share.

We are all so pressed for time, anxious for whatever comes next. They will indeed sell you anything if they can make it for less. Buy it, it'll buy you your name your face for show buy, you lucky fool, your place to go. You'll get there soon through (pick your favorite) means you'll advance your train of chicken marks, counted off by twos and threes hopping steps with long and eager strides hurry to the end, it's sure to please. — Deborah A. Smith, 1981